I have now spent nearly 1.5 years in China. I thought it fitting that I take some time to try to remember the things that were shocking to me when I first arrived, before everything becomes normalized to me.

You Can Turn Around Wherever the F*** You Want

Without question one of the most shocking things about China is the culture of driving. It is simultaneously terrifying and amazing. There are two simple rules that everyone follows to the letter: 1, do whatever the f*** you want. Now obviously I exaggerate a bit for effect, but compared with the US, it certainly seems to be a laissez-faire driving environment. You can get into the other lane whenever you want, pull a three-point turn in the middle of a busy thoroughfare, or make right turns whenever other people are going that way, or turn left against traffic on green. This works because of the next rule: 2, be prepared to stop on a f***ing dime. In this regard, Chinese drivers are surely among the best in the world. Everyone is sublimely excellent at watching their own asses. Chinese drivers are incredibly alert. Every single time I take a car anywhere I witness behavior that would without question cause an accident in the US. But in China, it doesn’t, because the drivers are just excellent.

Pollution is Serious

Despite declaring a war on pollution and having a lot of success in tackling it, China’s pollution is still really bad. I reside in one of the best areas in the country for pollution, but still experience days that are rated as “very unhealthy” according the World Health Organization Standards. And unfortunately, despite constant moves toward green energy, China is still building an enormous number of new coal-powered plants – equal, in fact, to the total amount that the rest of the world has taken offline in recent years, meaning that a whole lot of the successes that western environmental movements have made in reducing carbon emissions will essentially be neutralized in the next few years.

The Old China is Still Around

Despite acclamations of the rise of New China, even here in the heart of Shanghai you find tiny little shops filled with hand tools and artisans. Nevertheless…

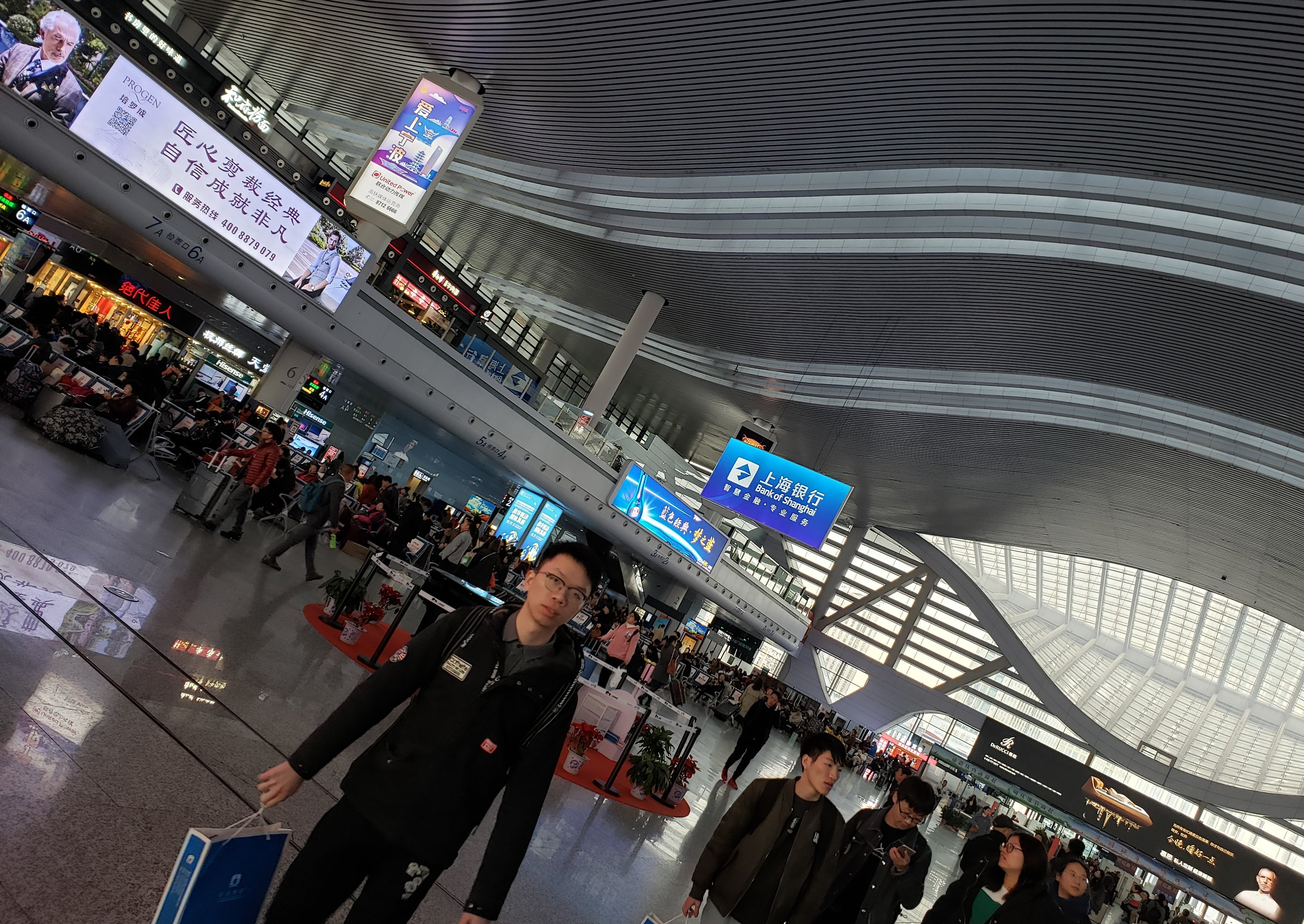

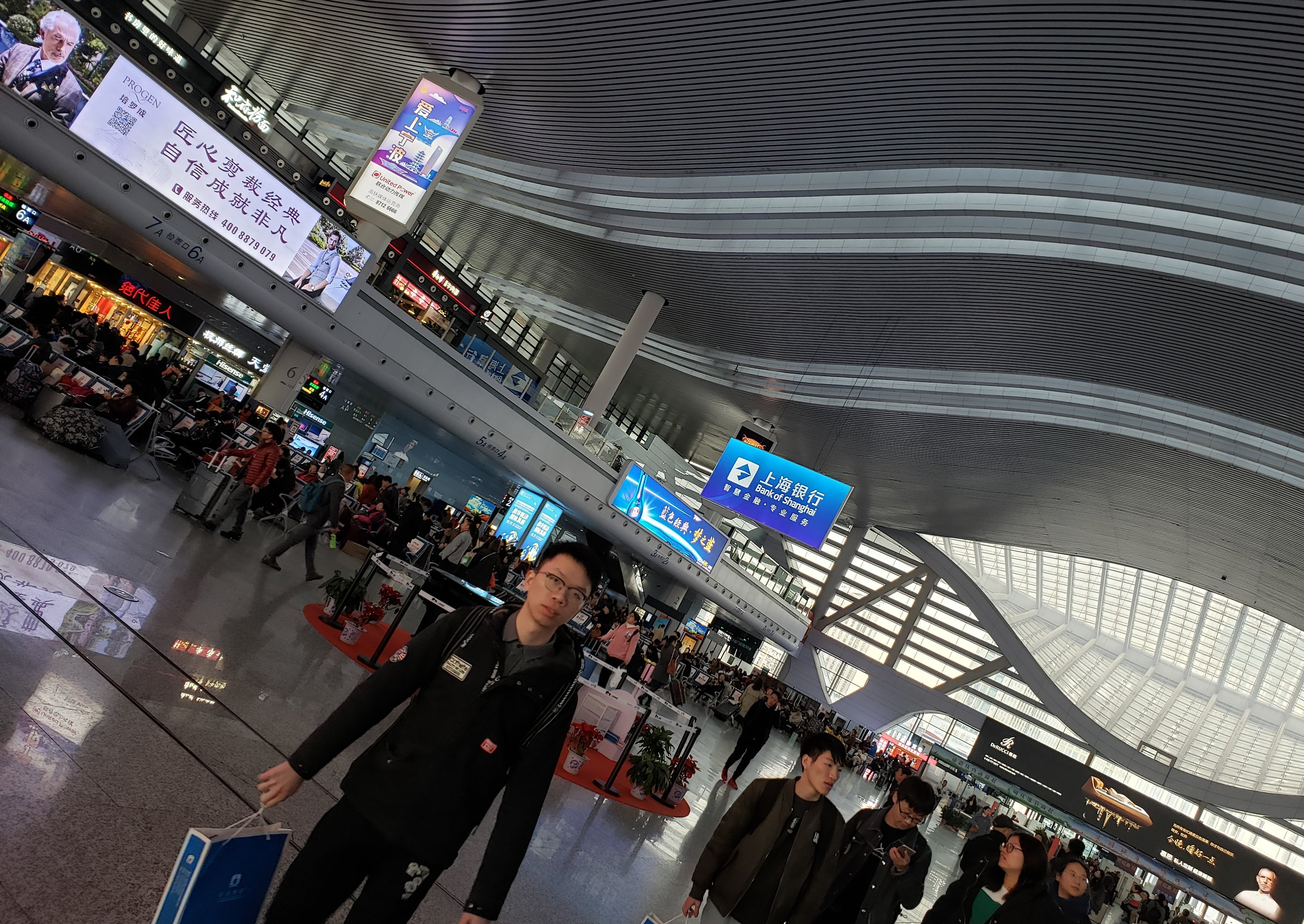

The New China is Big and Beautiful

China is heaven for fans of modern monumental architecture. Interior spaces are utterly massive, and many have incredible lighting and exterior design. Every time I look at a Chinese skyline at night I feel that the cityscapes – even in smaller towns – have overshot the visual aesthetics of sci-fi worlds like Blade Runner 2049 in their attainment of senses of superhuman grandeur. But these imposing edifices are thrown into even starker relief in places where…

Old and New Sit Side-by-Side

One hears this truism far too often, but it is far too true. Much of China’s development has been haphazard, and high-tech commercial areas sometimes happen to spring up very near to ancient monuments. Shanghai is one such example, where dozens of temples around the city sit nestled among skyscrapers and Buddhist monks bump elbows with CEOs on the sidewalk. In fact it’s hard not too, considering that

Chinese Crowds are Next F***ing Level

One knows that China is heavily populated, but the extent to which that is true eludes the imaginations of those who have never been there. If you dumped the entire population of Europe and Latin America into the United States it would still be hundreds of millions shy of the population of China. And it’s mostly concentrated in cities. 6 of the 10 most populous cities in the world are in China, including spots 1, 2, 3, and 4. You could triple the downtown population of New York City and it would be only about that of Shanghai and still far under Chongqing. You do not know crowded if you don’t know China crowded. Which can get extremely unpleasant when you factor in the facts that:

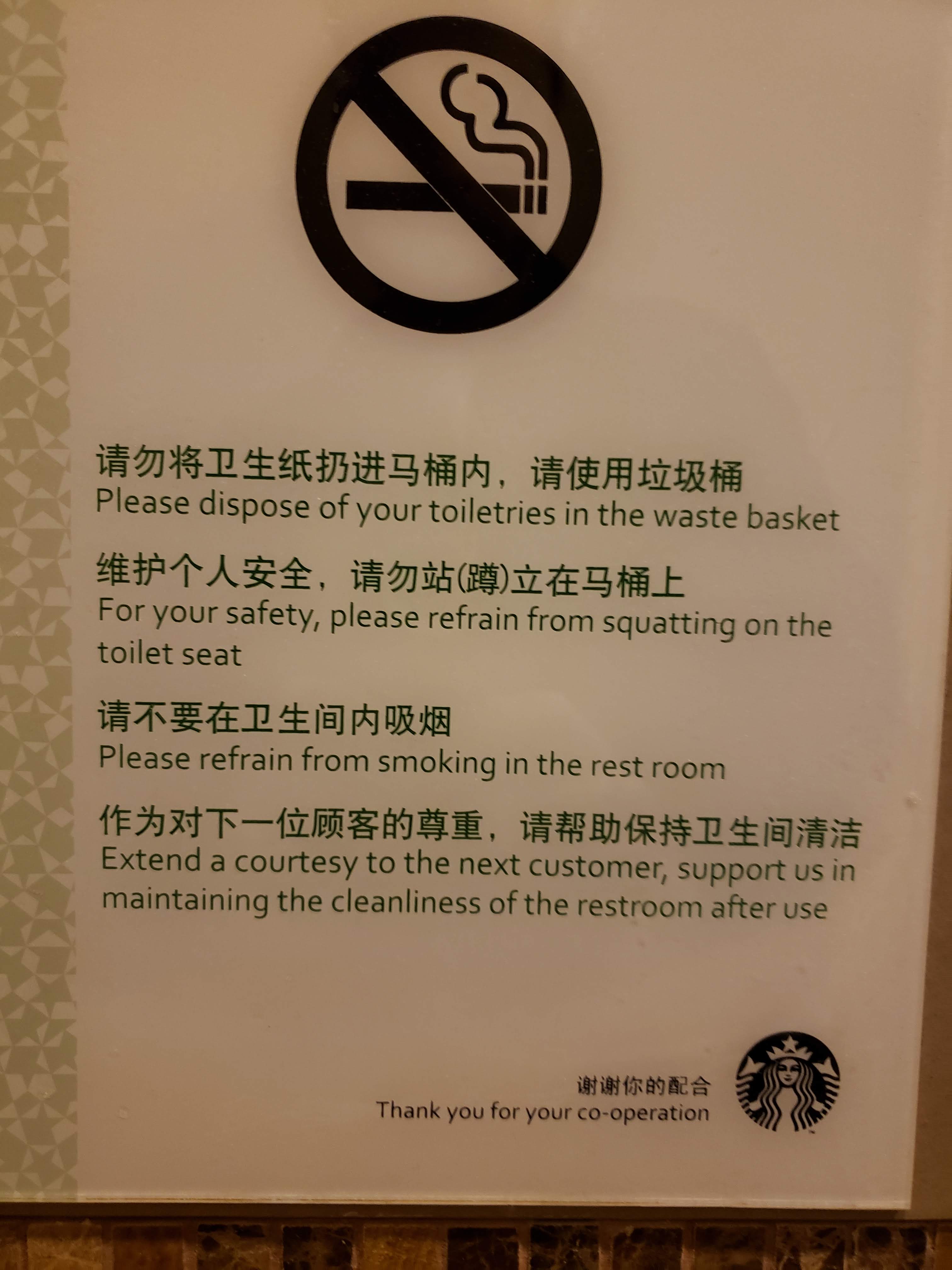

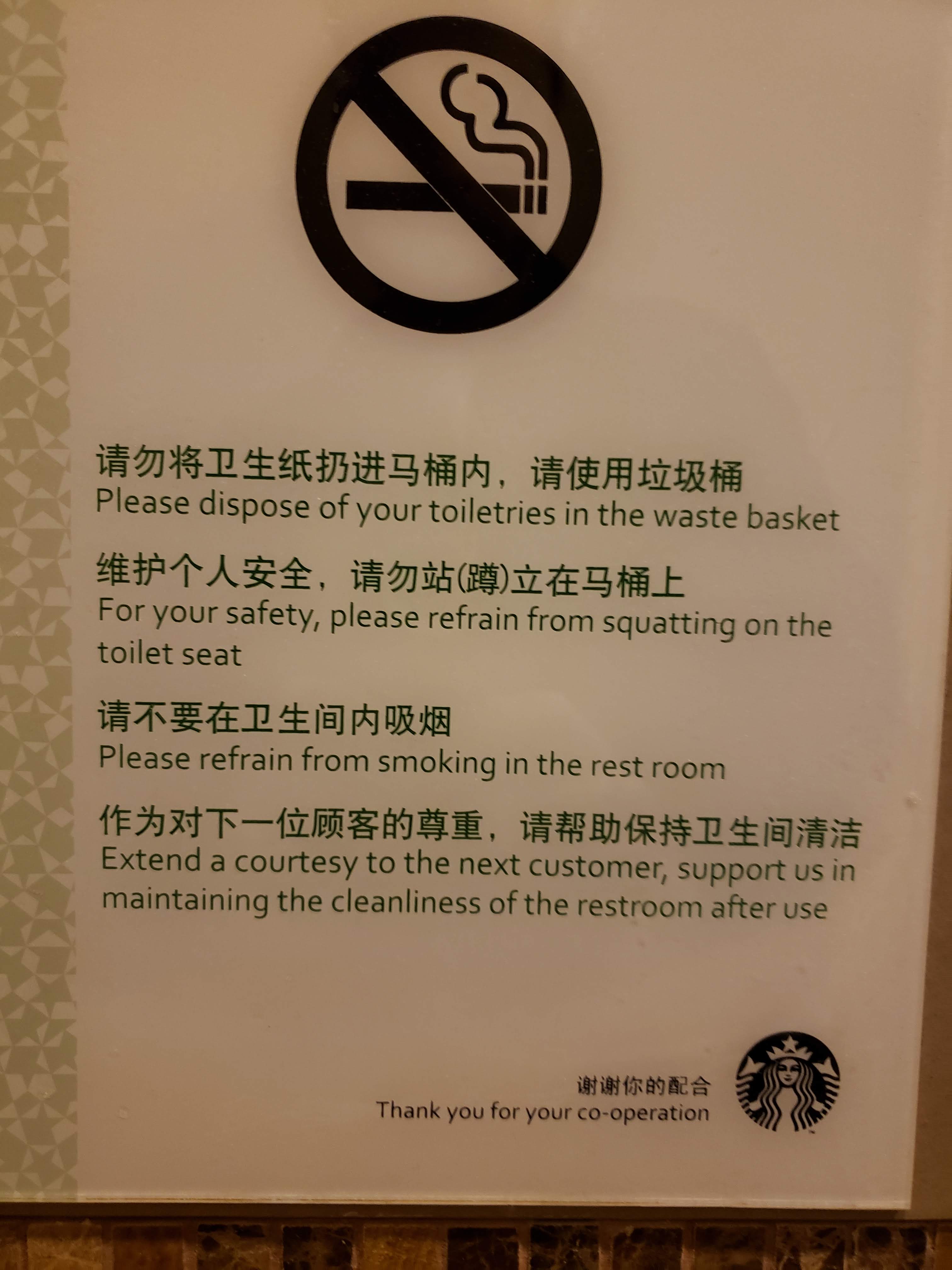

Smoking is Ubiquitous

What’s that guy doing?

Picking out fruit in the fruit store. While smoking a cigarette.

What’s this guy doing?

standing next to a no-smoking sign. While smoking a cigarette (I asked this person if he could read, and he just glowered at me). More than a third of the Chinese population smokes (however this statistic exhibits strong sexual dimorphism, with the rate for Men being over 50% and that for women being under 5%) . I have heard anecdotally that one reason for the high smoking rate is that cigarette sales taxes are a huge source of revenue for local governments, but I do not understand the structure of Chinese civic finance enough to verify or refute that assertion. However, I have recently noticed a sharp uptick in the number of anti-tobacco messages through various channels. No-smoking signs exist in most of the places you would expect to find them in the West, but they are routinely ignored as a matter of principle, to the extent that I have taken to using the simile, “as useless as a Chinese no-smoking sign”. It is particularly accepted – to the extent that it is essentially the rule – to smoke in bathrooms, and every train station bathroom I have ever been in has reeked of cigarette smoke. Despite the signs.

Squatty Potties

One hears about there being squatting toilets in China. However, a typical reaction is to assume that they are the old style toilets of poverty, and that modern toilets are new and sitting-style. This is absolutely not the case: the squatting toilet featured here is on a new model high-speed train. Many people simple prefer the squatting potties because they can actually help with defecation. The problem, however, is that many people take that preference so strongly that they insist on squatting on western-style sitting toilets, such as the one at the Starbucks where the sign was posted. Starbucks felt the need to respond to that proclivity with the second point on the sign listed here.

Cherry Tomato is a Fruit

There is an aphorism in English that “intelligence is knowing the tomato is a fruit; wisdom is not putting it in a fruit salad”. The Chinese would take great offense to that, as cherry tomatoes are regular features of fruit salad – in fact one of the most common ingredients. Cherry tomatoes are featured atop fruit pizza, in yogurt, and even candied to sprinkle atop ice cream. In case you’re wondering, they’re no sweeter than American varieties; in fact, I’ve had many varieties in the US that were far sweeter and less tart.

Eating on the job in professional settings

What you see in this photo is a pharmacist, in her lab coat, in a store that is open for business, eating her dinner with a companion in the middle of the store. This behavior is extremely common. There is no shame or embarrassment or even an attempt to hide it behind a counter. Nope – plonk a table down in the middle of the store and chow down.

White people for advertising purposes

It may be somewhat hard to see in this photo, but there are three white people used for advertisements in this photo – one in the bottom right and two at the top left. Regardless of the product, white people are often used to give a luster of quality and classiness to a product, particularly older white men who look like they could be professors. Though the official line is that China must walk past the West, in practice a lot of Western things are still celebrated as ideals.

Atypical food combinations

What, you don’t put cheese and mustard on your waffles? What about mayonnaise and corn on your pizza? How about espresso lemonade, beer-flavor latte, or yogurt and green tea? For me the things that are completely foreign in China are not shocking; it’s the the complete re-appropriation and recombination of Western foods that makes me do a double-take. And although it’s usually shocking, I’m constantly appreciative of the willingness to completely reimagine the artificial boundaries we place on food in our own cultures.

Very strong opinions about borders

China does not see eye-to-eye with its neighbors regarding where international boundaries lie, and makes sure to defend its position at every opportunity. Legally, all maps and globes printed in China must display the government’s official opinion on borders, including the famous nine-dash line of maximalist claims in the South China Sea (reaching all the way to the coast of Borneo). And by all maps, I mean all maps, even novelty things or those in a children’s movie. In fact, these kinds of things are perhaps most important of all from the perspective of the government: it’s important that kids be raised from birth always seeing the maximalist territorial claims, always believing such positions as “Taiwan is an inseparable part of China”.

A lot of dress-up

Many people like dressing up in, let’s just say “atypical” clothing in China. The two most common kinds are this kind of Victorian Doll type getup as seen here, or more commonly “Hanfu“, “Han clothing”, an anachronistic mishmash of any kind of historical attire worn in China from really any pre-modern period. As long as it looks historical and Chinese-y. This movement is often, but not always, associate with a Chinese nationalist movement to reject Western-influenced attire.

Lots of thermoses

This photo depicts a thermos store. A store…entirely of thermoses. This was not even the only one in this particular mall. Many Chinese carry thermoses ubiquitously, usually filled with tea leaves, and no airport, train, or waiting room is complete without a complementary hot water dispenser so that people can top-up their tea bottles. In literally every taxi I have ever been in in China, the driver has a thermos full of tea (this is not always the case for Didi, the Chinese Uber clone, for some reason)