A short intro to the philosophy of ethics

J.R.R. Tolkien maintained a very private, but very negative opinion of Frank Herbert’s Dune. In Tolkien’s Library, entry 964, Tolkien is quoted as having written in an unpublished letter to John Bush, on March 12 1966, “It is impossible for an author still writing to be fair to another author working along the same lines. At least I find it so. In fact I dislike Dune with some intensity, and in that unfortunate case it is much the best and fairest to another author to keep silent and refuse to comment”. [EDIT 21 March: A comment noted that “hated” is too strong a word – see my comments at the end for a defense of my word choice.] Tolkien does not elaborate, leaving the reasons for his intense dislike as an exercise for the reader. However, when one peers under the hood into the underlying philosophies of the two authors, one can easily imagine the answer: Herbert and Tolkien are exact moral opposites. Tolkien was an avid Deontologist and Dune is pure Consequentialism.

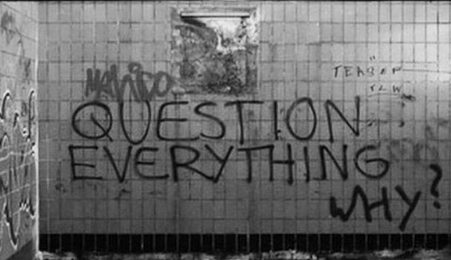

Deontology and Consequentialism are two of the biggest rival camps in ethics. Deontology (from Greek: δέον, ‘obligation, duty’ + λόγος, ‘study’) says “acts are in themselves either good or bad”, whereas Consequentialism says “whether an act is good or bad depends on the consequences”. The central message of Tolkien’s work, hammered again and again and again, is that one should be a deontologist, a simple, good person who does charitable and good things, and that where evil arises in the world it is not the result of being inherently “bad” but rather by being convinced that one can commit small acts of selfishness and vainglory that one is convinced work toward a greater good. As Gandalf, speaking with the author’s voice, no doubt, says, “Many that live deserve death. Some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them, Frodo? Do not be too eager to deal out death in judgment. Even the very wise cannot see all ends.”

Dune is much the opposite. The Dune saga focuses on the morality of consequence, the tradeoffs of rule, the interactions of large and often amoral systems, the ways in which a man wields these powers to achieve his goals, and the way in which the long-term consequences of his actions determine his ultimate moral worth. Herbert writes, “Greatness is a transitory experience. It is never consistent. It depends in part upon the myth-making imagination of humankind.” That is to say, greatness depends on human perspectives; if people perceive something as great, it is great, and that opinion can change over time as morality evolves.

We can see already that this morality diverges from Tolkien’s simple, deontological “slave morality“, in which greatness does not depend upon the spirit of the times, but rather embodies a spirit that stands the test of time, a prototype of Captain America’s famous “no, you move” monologue. To wit, consider Aragorn’s rather direct opposing quote, “Deeds will not be less valiant because they are unpraised” (RotK). One might argue that Herbert explicitly deconstructs the Tolkeinesque hero embodied in Leto (I) Atreides, whose valiance and refusal to embrace Machiavellian calculus, his staunch clinging to his personal and family honor, ultimately cost him his life. But the moral disagreement between Herbert and Tolkien goes much deeper.

Though there is no evidence that Tolkien continued to read on in the series (indeed he passed away in 1973, so could not have read beyond the second book, Dune Messiah, though since he disliked the original it would be odd for him to read on), those who have read past the introductory books up to God Emperor of Dune (it was introduced in Dune Messiah, but its full elaboration was only given in GEoD) know about the so-called Golden Path. The Path is, in short, a path to avoid humanity’s extinction. Leto II views the eventual extinction of humanity as something to be avoided at all costs, worthy of all sacrifices, and as such the Golden Path – his plan to so brutally oppress humanity that future humans would go their separate ways and refuse to ever submit themselves again to centralized rule -is pure, unadulterated consequentialism – the ultimate, millennia-long evil, countless acts of barbarity and oppression, to achieve a possible good. As Leto II extols, “I have been called many things: Usurper, Tyrant, Despot. Some even call me the greatest mass murderer in history. They are not entirely wrong. My actions have caused great suffering, and I bear that burden willingly, for I know that the future of humanity depends on it.” In other words, the ends justify the means. And thus the zenith of necessary ends justifies the nadir of abhorrent means. We need not even imagine what Tolkien thought of this: Gandalf (as we mentioned earlier, Tolkien’s surrogate), addresses it: “It is not our part to master all the tides of the world, but to do what is in us for the succor of those years wherein we are set, uprooting the evil in the fields that we know, so that those who live after may have clean earth to till.”

The philosophical disagreement between Tolkien and Herbert touches on many more subjects, of course, and another prominent disagreement was that Tolkien was a very devout Catholic and Herbert was not exactly friendly towards religion. Herbert saw religion as an inherently mutable, utilitarian institution, and Herbert was dismissive or even openly antagonistic toward religious truths. In the world of “Dune,” religion serves as a powerful tool for control and manipulation, with institutions like the Bene Gesserit using it to shape political and social outcomes – indeed the central prophecy (that of the Lisan al Gaib) of the original book was a completely artificial contrivance for political machinations of the Bene Gesserit. In contrast, of course, Tolkien saw Christianity as channeling eternal moral truths about kindness and redemption, and his world-building reflects his belief in a higher power and cosmic order, with themes like mercy, sacrifice, and the triumph of hope over despair mirroring his theological perspective.

Religious differences aside, the central argument between the two authors is the moral one. Tolkien is a modernist (or even pre-modernist); Herbert is a post-modernist: Tolkien encourages everyone to follow a single template of goodness; Herbert encourages cynicism and doubt of the institutions that produce templates, and shows the anguish experienced by Paul when he is forced into a template to survive. If one had to summarize these different perspectives in one sentence, Tolkien argues “Strive for goodness, and people will come to call it great”, whereas Herbert argues “strive for greatness, and people will come to call it good”.

Edit 21 March: A Defense of the term “hated”

As mentioned above, a post on https://potbanks.wordpress.com/category/tolkien-gleanings/ took issue with the term “hated”, finding it mischaracterized Tolkien’s feelings, which, as he himself wrote, were “strong dislike” not “hate”. However, I do believe that the word “hate” does not have nearly the same meaning as it did in the 1960s when Tolkien penned his comments, and certainly not the same as it did earlier in the century when Tolkien was developing his own ideolect and semantic impressions. It is a word that has undergone a great deal of semantic inflation, and is thus much weaker than it used to be – according to Google Ngram viewer it took on a new life after 1980 and is is more than three times more present in common usage today than it was in 1920. Someone born since 1980 – most blog readers – would likely use “hate” to express the same intensity of emotion for which someone born in 1892 would use “dislike”, let alone “strongly dislike”.

The commenter mentioned that the title is “clickbait-y”, and this is not entirely wrong, because the era of clickbait is both a contributor to, but also a result of, the aforementioned semantic inflation. On the one hand it is true that an article titled “Why Tolkien Disliked Dune” would bait fewer clicks than one that uses the term “hated”, on the other hand as mentioned above the choice of words is merely keeping step with what is a living and evolving language. Phrasing the title as “Hwætforð Tolkien āsċūnode Dune” would be even less clickbait-y.