Or one way illiberal states get the better deal on trade agreements

A concept that I would have imagined was thoroughly discussed, but which I somehow cannot find discussed anywhere, is the concept of culture as a trade barrier. Now the idea that culture affects trade is nothing new – no one ever claimed that every country should buy equally all the products of the world; culture is a normal and expected part of the global marketing and trade landscape. But what I have never seen discussed is the extent to which culture can act as a hard barrier which can act one way more strongly than the other, or as one that is malleable for the purposes of statecraft – particularly in the hands of totalitarian societies that can shape public opinion and craft cultural trade preferences more easily than democracies.

What I mean when I say that culture can be a trade barrier, and often should be studied and analyzed as one, is this: different peoples in different countries tend to buy different things. Sounds simple, right? But it’s not simple. Some cultures can be very fussy about the products they consume coming in particular forms or from particular places, and these preferences can make foreign producers of ostensibly similar products (replacement goods, to use the formal term) have to fight uphill battles to get their products into those markets, even if there’s not an equivalent in the other direction (I list several examples below). These preferences can take many different forms: sometimes people tend to buy things that are from their own country, or tend not to buy things that are from a specific country, for completely irrational reasons or even without any particular reason, just by background cultural “by-default” programming. Or sometimes, because of the cultural traditions and preferences of the country, there may be an extreme difficulty getting the citizens of the country to buy things from somewhere else. Critically, these preferences are not fixed, and are susceptible to marketing campaigns, but are equally susceptible to state programs of marketing or propaganda (depending on your perspective).

Nationalized Preferences

For an example of “national preference” trade barriers, we need only think of “buy American” campaigns. In the context of World Trade Organization or other free trade agreement (e.g. the European Union or USMCA), national governments have their hands tied on providing direct subsidies, protections, and benefits to the industries covered by the agreement. For example, if it is agreed that countries should trade bicycles without trade barriers, it would be a violation if a party to the agreement were giving government subsidies to their domestic bicycle industry, or doing something to restrict the imports of bicycles, causing an unfair advantage in their competition with trade partners; the WTO has mechanisms for levying punishments on violations by members. However, countries have the possible workaround of trying to shift national preferences. A campaign encouraging people to “buy American” can potentially have small effects that shift buying preferences and result in some difficulty in non-American products competing in certain contexts – a slight raising of the cultural trade barrier. Though in practice these campaigns don’t have much effect in the US, in other countries waves of national sentiment can constitute huge trade barriers: the Chinese government has long fanned the flames of anti-Japanese sentiment, causing Japanese shops and factories to be damaged and close due to Chinese protests, and even causing rebranding of Chinese brands accused of being “too Japanese”; when this happens, Japanese sales to China of many goods predictably fall. Critics may argue that preferences of national origins are often “signals” of quality (i.e. with no further information about products that appear identical, most western consumers would likely judge “made in China” to be lower quality than “made in Germany”), this is not a 1:1 correlation with preferences for buying things from a specific country – people may choose to buy from one’s own country even if it doesn’t mean cheaper or better quality, or buy from “friendly” countries over “unfriendly ones” as seen by American boycotts of French-sounding products at the outset of the Iraq War. So clearly there is something else going on aside from signaling.

Denationalized Preferences

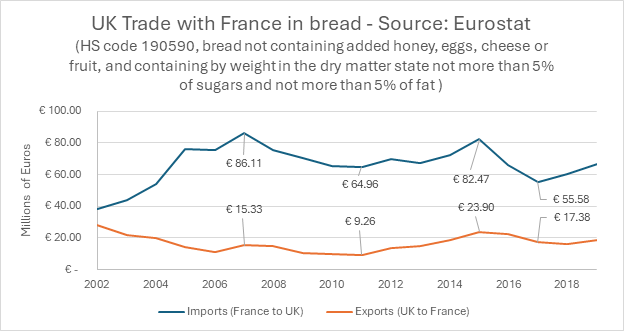

For the denationalized “cultural preference” barrier, take milk for example. In country A people may be perfectly willing to buy and use UHT (Ultra-High Temperature pasteurized, i.e. shelf-stable) milk as any other milk. And in a neighboring country B people may overwhelmingly prefer to use fresh, refrigerated milk. As a result, country B can UHT-pasteurize and export all of its excess milk production into country A, but country A will have a much harder time shipping fresh milk to country B at affordable prices, since such shipments would require refrigerated trucks and much more efficient logistical planning to ship the milk larger distances over international borders. Thus, the culture of country B constitutes a form of trade barrier relative to that of country A. For a data-backed real-world example, consider the preferences in bread consumption of France versus the UK. In the UK, bread is often consumed, as in the US, in a soft, pre-sliced form, easy to pop in the toaster for breakfast, and just as easy to keep fresh on the shelves for days on end; in France, bread is by and large consumed fresh, with a crackly-crusty exterior while still being soft on the interior, a juxtaposition that breaks down within hours if wrapped in plastic, or becomes too dry and hard if left unwrapped – in short, impossible to pack and ship internationally. As a result, we got the following (before Brexit):

French exports of bread to the UK dwarfed the inverse – France could produce and ship the kind of bread that Britons wanted to eat, but the UK couldn’t produce and ship the kind of bread that French wanted to eat. Thus French exports to the UK were, since 2005 or so, 3-6x UK bread exports to France. There are certainly other possible explanations for this phenomenon, but I imagine that the cultural barrier is a significant one.

Another notable real-world example, though slightly more abstract, was salmon. Prior to the 1990s, Japan consumed very little salmon and almost exclusively in a cooked form, viewing salmon as a fish prone to parasites that should not ever be consumed raw, whereas in Norway raw or lightly smoked salmon is a staple of the national cuisine. In the late 1980s, Norwegian fishermen found themselves with a surplus of Salmon and insufficient markets to offload it into, and thus they sought to change the culture of Japan through a fierce marketing campaign that transformed the culinary culture of the land of the rising sun – salmon sushi is now arguably one of the most iconic emblems of Japanese cuisine. The culture of Japan constituted a trade barrier, and clever Norwegian marketing lowered, or even reversed, the cultural trade barrier.

The Illiberal Advantage

As I mentioned, one aspect of this discussion – the impacts of culture on trade – are nothing new. But what is often missed from these analyses is that it does not operate equally for all countries – some countries have much stronger cultural “walls” than others. It stands to reason that authoritarian regimes with tight media controls (e.g. China) have much more power to shift culture in a direction that brings economic benefit – for example, encouraging Traditional Chinese Medicine as a way of stimulating the domestic market and raising a trade barrier to foreign pharmaceuticals, or perhaps doing behind-the-scenes manipulation to discourage state-affiliated firms (increasingly all major Chinese firms) from buying from geostrategic competitors. As such, liberal democracies have a strong incentive to understand this greater power of their non-democratic rivals and trade competitors to shape tradeflows and effectively circumvent and nullify aspects of free trade agreements. A solution would be to create monitoring offices at the WTO or embedded in trade agreement arbitration mechanisms to set limits on the scale or intensity of marketing campaigns or state manipulation of cultural preferences that affect trade.