Tyler Cowen recently posted on Marginal Revolution the question “How Important is the ‘scientific method’?” This called to mind the following paper I wrote several years ago in which I analyzed how many of the most important scientific discoveries of all time had come about from scientists who eschew “good science” and follow their hearts, biases, convictions – whatever you want to call them. Since writing this analysis, my opinion on the matter has ebbed and flowed – I think increasingly we need to turn to established institutions and procedures to help navigate the rising tide of disinformation, fake news, and fake science, but at the same time I think we must be more skeptical and critical of such institutions as they do maintain the ability to shut down dissenting voices or heterodox research. The recent Washington Post article on heterodox research in anthropology/archaeology is a great case in point. Open sourcing the publication and peer review of research, as the article illustrates, is one possible avenue, but does that solution prevent or facilitate the capture of those review processes by bad actors (botnets, special interests, internet vigilantes)? Without question the world is heading toward a fundamental restructuring of core processes and institutions that have served us well for centuries, and Western Civilization is facing its greatest epistemic upheaval since the Protestant Reformation. For those of you seeing this blog for the first time, that is a core theme of my writings. For other articles touching on this theme, check out this, this, or this.

Without further ado, my paper to the point:

Scientific progress comes in a variety of forms, be it via flashes of inspiration, methodical research and investigation, or simply the products of fortunate accidents. Nevertheless, through the history of western science, certain standards have arisen regarding the way in which “true” science should be done. The scientific method remains the centerpiece of these standards, stressing repeated observation, testing of hypotheses both new and old, and checking our assumptions against the realities of the physical world. In general, it is also considered standard to report all findings, whether they support current theories or not, and thus manipulation and selection of data to support preconceived notions is frowned upon, and generally considered unscientific. This stance, however, is the ideal; in reality, manipulation and staging of data has given us some of the greatest scientific breakthroughs in history – and perpetuated some of the worst misconceptions. The question, therefore, is not whether manipulation takes place in good science, but why it takes place and how science can be good despite it. Ultimately, we find that selection and staging of data has occurred throughout modern science, and that the reasons for it are based not on failures of the methods and standards of scientific practice, but rather on external social and personal influences which take advantage of the fact that science is, at its core, a human endeavor.

In their critical analysis of the history of modern science, The Golem, authors Collins and Pinch discuss at length the 19th century debate over spontaneous generation versus biogenesis, and the role that Louis Pasteur played in the battle of scientific viewpoints. The account provides an excellent illustration of how good science can still be wrong, while “impure” practices can still illustrate the truth. Pasteur’s rival, Felix Pouchet, a staunch proponent of spontaneous generation, conducted a series of experiments to prove that life could arise from non-living material. His results were fully documented, and his experiments always showed the rise of life from his supposedly sterilized materials (Collins and Pinch 84-86). On the other hand, Pasteur conducted many experiments, of which some also seemed to show abiogenesis. Pasteur conveniently disregarded those experiments, only publicly reporting those outcomes which supported his hypothesis; “he did not accept these results as evidence of the spontaneous generation hypothesis” (C&P 85). Ultimately, Pasteur was able to align the scientific community in his favor, and biogenesis became the accepted theory of the propagation of life (C&P 87-88). The question this requires us to ask, though, is how selected and staged data ultimately came to be proven correct. Clearly, Pasteur’s methods broke with “standard” scientific practice even in the 19th century and even more so today, so there appears to be no direct connection between factual accuracy and adherence to the scientific method. Yet the scientific method remains the cornerstone of scientific research and investigation, so perhaps there is more to the nature of science than the example of Pasteur can adequately illuminate.

Perhaps a more blatant example of staging and manipulation is that of Arthur Stanley Eddington and his astronomical expeditions in 1919. Determined to prove Einstein’s theory of relativity correct, Eddington and his fellow researchers set sail for the equator to make observations of a solar eclipse, a unique opportunity to test relativity’s predictions of gravitational lensing. The expedition’s observations, however, seemed vague, with some observations supported Einstein’s predictions, others Newton’s (C&P 48-49). Eddington chose only to publicize those data which supported Einstein. His reasons for this are mixed, and both The Golem and Matthew Stanley’s article explain his staging in different ways. The account from The Golem portrays Eddington’s thought process as simply ignoring systematic errors and focusing on those results which seemed devoid of irregularities; as a result he was conveniently left with those results which confirmed relativity. By that account, Eddington was doing “good” science, because he knew well the objective realities of his work, and was able to determine what data should and should not have been taken into consideration.

The Stanley article, on the other hand, paints a very different picture of Eddington and his motives. The article notes that prior to the time of Eddington’s observations, international science had grown petty and nationalistic, in many ways tied to the bellicose technological advances during the First World War. The horrors which destructive technologies such as the battle tank, advanced artillery, and poisonous gasses had wrought by the end of the war led to public apprehension and disdain toward scientific achievement (Dr. Ralph Hamerla, Lecture). According to Stanley, Eddington sought to change that sentiment. Raised a Quaker, and thus with a more humanistic and anationalistic outlook, Eddington sought a transnational approach to solve the problems of mankind (Stanley 59). He believed that a British expedition into Africa and South America to confirm a German’s theory would speak volumes for the international approach necessary for beneficial scientific advancement (Stanley 59). In light of Stanley’s article, then, Eddington maintained a personal motive and religious background which may have biased his observations and decisions regarding the staging of his data.

This brings us to an important question about not only Eddington, but manipulation and staging of data in general. Are data and observations manipulated intentionally and consciously by those who present them, staged because of subconscious influences, or is there more to the matter than that? Returning to the example of Pasteur, The Golem reveals that “Pasteur was so committed in his opposition to spontaneous generation that he preferred to believe there was some unknown flaw in his work than to publish the results…He defined experiments that seemed to confirm spontaneous generation as unsuccessful, and vice versa” (C&P 85). Here, then, is another example of a scientist who does manipulate and disregard data in a conscious way, but not for any conscious reasons. Rather, his preconceived notions about what was to be expected influenced his interpretation of the data. Eddington’s actions likely followed a similar path. His Quaker, internationalist attitudes and desires may have subconsciously caused him to see systematic error in the observations he made, and those observations which confirmed relativity appeared relatively flawless to him. It is always possible, however, that he made his interpretation purely out of scientific objectivity, but Pasteur’s example seems to make the first possibility more likely.

These examples cannot be taken to imply that manipulation is always done without conscious intent, however, nor that such staging of data always contributes to a better understanding of natural realities – quite the contrary on both counts.

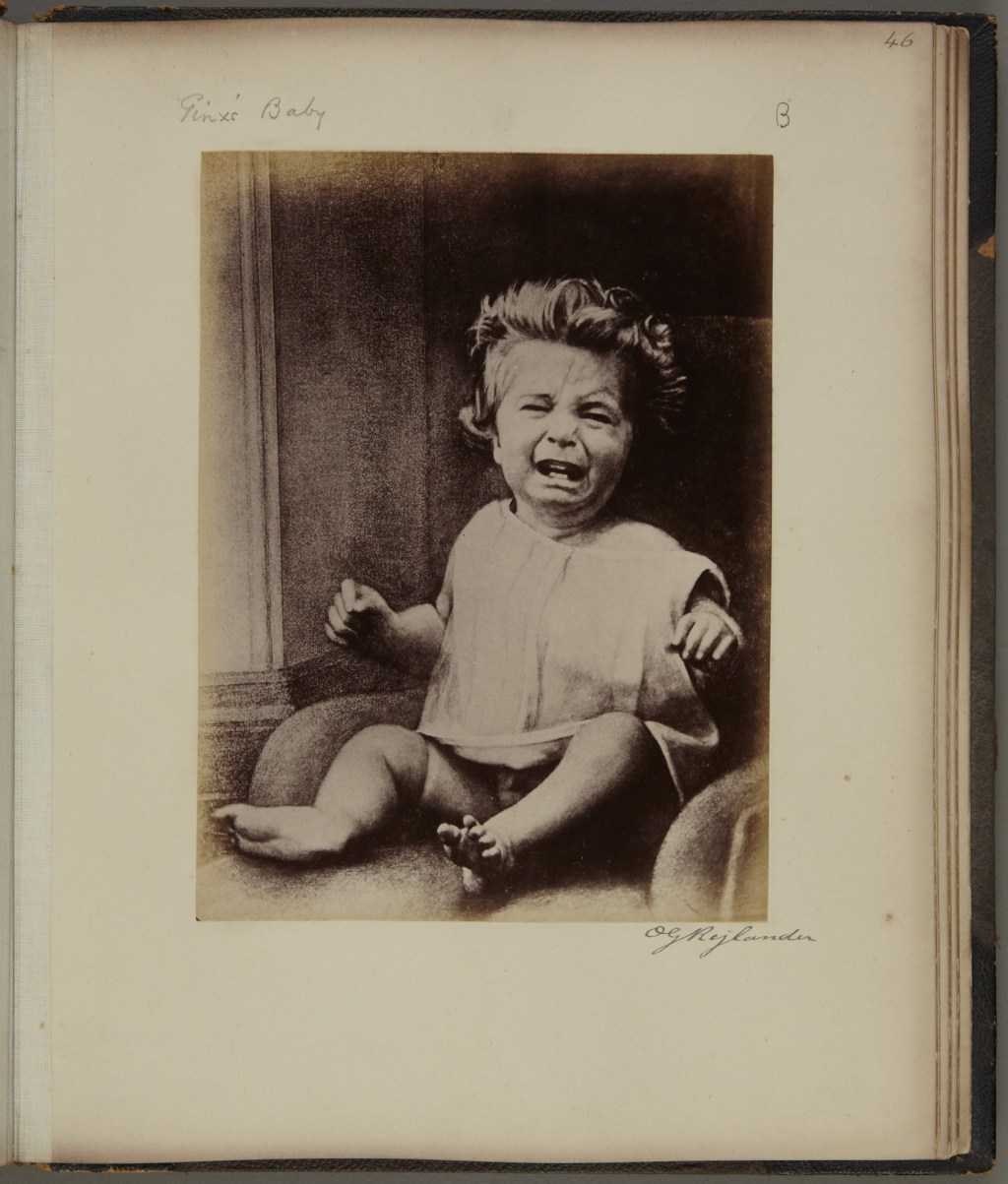

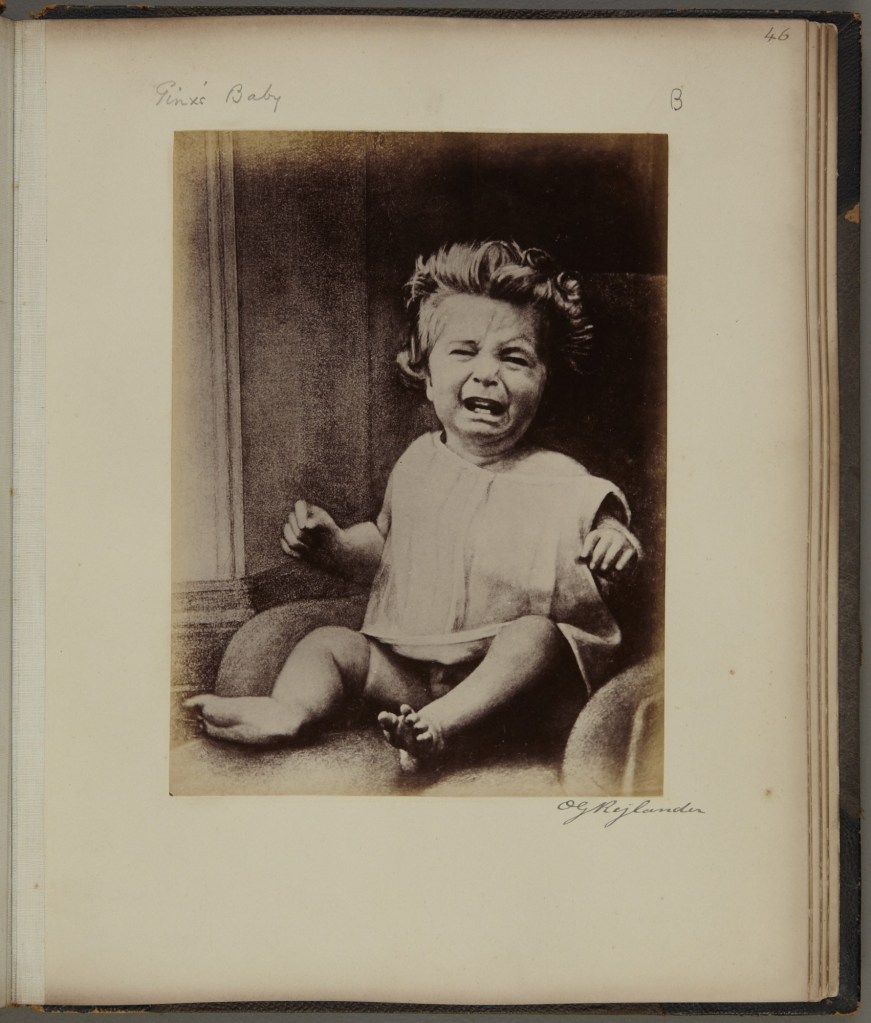

Though one could imagine that a conscious manipulation of data and figures would be intended to change the perceived outcome of the experiment, Charles Darwin used staging to the opposite effect: to better explain the argument he was already making, from the conclusions he had already drawn. Philip Prodger’s “Inscribing Science” addresses the idea that Darwin’s intentions behind the manipulation of photography. In his The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (heretofore “Emotions”), Darwin makes great use of the then-fairly-new medium of photography to provide actual images of expressed emotions in people. As Prodger asserts, “His photographic illustrations were carefully contrived to present evidence Darwin considered important to his work” (Prodger 144). Given that the medium was relatively new at the time, it had its limits in terms of both detail and exposure time, “in the order of tens of seconds” (Prodger 156). As a result, some tweaking, staging, and manipulation were necessary to accurately convey Darwin’s selected evidence. He collaborated with both Oscar Rejlander and Duchenne de Boulogne in generating images for Emotions, with the former providing photographs of posed emotions, and the latter, photos of electrode-induced facial expressions. Darwin manipulated both for his book. In the case of Rejlander, Darwin removed electrodes and scientific equipment from the photos, leaving only the induced emotion visible in the book (Prodger 166-169). One of Rejlander’s photographs, known as Ginx’s Baby, was so important for the book that Darwin created a photograph of a drawing of the photo, so as to ensure that all details of the image were captured perfectly (Prodger 173-5). At the same time, for the photographs produced by both men, Darwin changed the settings of the subjects, going so far as to place Ginx’s Baby into a comfortable chair.

Ginx’s Baby:

Darwin’s reasons for his manipulations seem obvious enough. The photography of the day, with its long exposure times and imperfect detail, was incapable of distilling the split-second nuances of human emotional expression. It was thus difficult to communicate, via photography, the scientifically important intricacies which Darwin needed to support his claim. However, he could observe these emotions and draw his conclusions from them as they happened. Thus, Darwin was not truly manipulating his data, merely the means by which he passed it on to others, casting serious doubt on the idea that he may have had coercive motives behind his alterations.

Innocence may be questionable, however, in the case of the alteration and manipulation of data relating to racism and biological determinism during the 19th and early 20th centuries. In The Mismeasure of Man, Stephen Jay Gould analyzes the manipulative means – intentional or otherwise – that racial scientists and craniologists employed in the dissemination of data relating to innate racial differences and phylogeny. His analysis of Samuel George Morton gives keen insight into the thought process of a blatant manipulator of data. In Morton’s presentation of data about average brain size among races, Gould states that he “often chose to include or delete large subsamples in order to match group averages with prior expectations,” that in his reports “degrees of discrepancy match a priori assumptions,” and that “he never considered alternate hypotheses, though his own data cried out for a different interpretation” (Gould 100). All of these cases seem to demand the inference that Morton was consciously and actively manipulating data to match his own preconceived notions about racial characteristics. Yet Gould himself takes the other side, stating that he “detect[s] no sign of fraud or conscious manipulation…Morton made no attempt to cover his tracks…he explained all of his procedures and published all of his data” (Gould 101). He comes to the conclusion that the only motivation behind Morton’s warping of data was “an a priori conviction about racial ranking” (Gould 101). Yet despite such flawed data, “Morton was widely hailed as the objectivist of his day” (Gould 101). The fact that he was hailed as such clearly demonstrates the degree to which bias and misconceptions permeated society. Based on his and others’ studies, craniometry and racial sciences perpetuated the ideas of white racial superiority well into the twentieth century.

We are therefore left with an indecipherable mixture of outcomes based upon the manipulation of scientific data that is generated in departing from the purity of the scientific method. With Pasteur and Eddington their assumptions about the “correct” outcome of their experiments allowed them to “know” which data to exclude and which to accept. Both were ultimately proven correct, but whether their correctness was due to their superior scientific understanding or pure luck is not an answerable question . With Darwin, his choice of manipulation was clearly intentional, but the purpose benign: to better communicate technologically limited evidence and proof. His conclusions regarding the related emotions in humans and other animals are now supported by overwhelming scientific evidence – thus his case was one of superior scientific understanding. In the case of Morton and the racial scientists of the 19th and 20th centuries, it is clearly visible that preconceived notions can lead science down the wrong path as well as the right path. In the scientists’ quest to prove assumed facts, they ignored alternate interpretations and, instead, caused the stagnation of “objective” scientific perspective in the area of human physiology and evolution, while perpetuating social ills for a century or more.

It can be seen that assumptions and a priori conceptions about an area of science can utterly change the scientist’s perception of the outcome. However, our initial investigation into the cause of these preconceptions has many possible solutions. Social and religious goals are possible answers, from the example of both Morton and Eddington respectively, but pride, arrogance, or simple variances in scientific understanding are equally valid conclusions. It seems foolish, however to assume that humans, who carry opinions and preconceptions in every area of their personal lives, could be capable of completely ridding themselves of those same opinions when it comes to the pursuit of science. One can conclude that as long as humans engage in the endeavor of scientific inquiry, they shall bring with them their imaginations, opinions, and cultural biases, but whether bringing those variables into scientific pursuits ultimately adds or detracts from the quality of human scientific achievement is a purely subjective matter that we cannot hope to settle through prattling verbosity.