The Global Context of the Continental Uproar

Farmers are special in a lot of ways. They receive enormous amounts of subsidies from governments in a way that no other industry does. In most industries, free trade agreements prevent member governments from giving government subsidies to their industries; these would be unfair advantages that defeat the purposes of trade agreements. However, agriculture is by and large exempt from these free trade agreements. Why? A lot of food is easily freezable, cannable, refrigerable, processable and shippable around the world, and if we had a world with fully free trade, imported food from Far-Eastern Europe, Latin America, Africa and South Asia would be far cheaper than domestic production, and the agricultural production of wealthy countries would go the way of the textile production of wealthy countries – i.e., it would be uncompetitively expensive except as niche and artisan purchases, and soon there would be very few farmers or agricultural production in wealthy countries.

And this is really bad PR, and, potentially, bad policy. Why? Countries like to be able to say that they can feed themselves. If the voting public in some countries got wind that their government approved a policy that made their country completely dependent on foreign imports to get fed, they would burn down the halls of power (though many wealth countries with high populations and low arable land area, like Japan or the Netherlands, have been deeply dependent on food imports for decades – and microstates like Singapore are completely dependent on exports for basically everything, one reason why small states are historically big proponents of free trade: they just can’t aren’t big enough for self-sufficiency to be a realistic goal).

But like I said, it’s not just bad PR, it’s also potentially bad policy. The Pandemic years were a wake-up call to many countries that it might not be a bad idea to make sure one’s supply chains were robust and that one’s stocks of essential goods were secure. The world witnessed (despite efforts at censorship) starvation in a modern wealthy city (Shanghai and other Chinese Cities) when draconian covid lockdowns strained supply chains to their breaking point. It has long been military policy of many countries like the US to ensure that their agricultural production would allow the country to feed itself in the event of a trade-destroying war, and this makes a lot of sense because the US could realistically defeat any conventional enemy in conventional war but if faced with domestic starvation would be crippled.

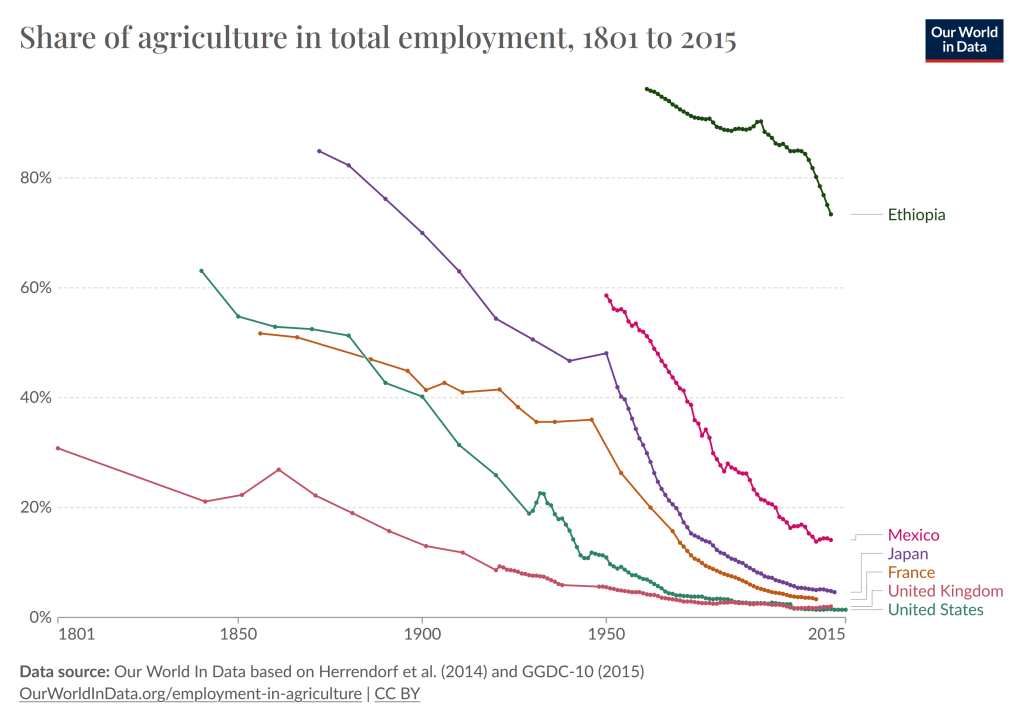

There’s also the pure PR power of farmers that makes them punch far above their weight in cultural and political discourse: except for the bluest of bluebloods, we all have farmers in our very recent ancestry, and until the 19th century most people in most countries were farmers.

Farmers are widely seen as embodying superhuman amounts of grit and humility, a winning personality combination in many countries. For all these reasons and more, their political clout is outsized.

Thus, many wealthy countries have gone out of their way to subsidize their agricultural sectors and keep farming productive and competitive – and farmers quiet. However, it has become increasingly apparent to policymakers that their treatment of farmers is potentially anti-environmental (https://whitherthewest.substack.com/p/the-danger-of-eating-locally) and inegalitarian. I’ll address each of these points in turn. Regarding the environment, farming can be highly polluting – not just via fertilizers and pesticides, but by outdated farm equipment; as an aside, I once heard a French farmer’s solution to a badger on his land was to pour gasoline into its burrow.

Regarding equality, remember how I said that wealthy countries want to keep agriculture out of free trade agreements so that they don’t get overwhelmed with cheaper products from Latin America, Africa, Far-East Europe and South Asia? Well, Latin America, Africa, Far-East Europe and South Asia are rather unhappy about that – agriculture is often their comparative advantage, and they find it deeply unfair that the things wealthy countries produce (manufactured goods) are subject to reduced tariffs, but the things they produce efficiently (agriculture and forest products) are magically kept out by tariffs for “nAtiOnAl sEcUrItY ReASons”.

This brings us to today. Many on the left side of the political spectrum in the EU are aware of these two issues (environment and inequality) and are pushing for changes that would not benefit the EU agricultural sector but would privilege environment and global social justice – reductions in subsidies, enforced environmental protections, and ongoing free trade negotiations with Mercosur (a Latin American trade bloc). With the latest push for the Green New Deal in Europe, farmers around the continent decided to see how much heft they had in the European political machinery. And it turns out, they have quite a bit, seeing as after only a few days of protest they secured key concessions from the French government – an exemption from the diesel subsidy phaseout, and continued “No” from France on negotiations with Mercosur. And European far right groups are linking arms with farmers, pushing for increased emphasis on sovereignty and territoriality against the “hegemonic” imposition of EU rules.

The upcoming European Elections will decide a lot of this – will the right’s courting of farmers work, or will Europeans tire of the antics before June rolls around – but to some extent the battle is already lost. The fact that left-environmentalism seems to see agriculture as fair game means that the PR armor of farmers has already been breached, and more reforms in the direction of both environment and global equality are likely to come in the future.