Update: please see the update note after the guide image for some additional arguments and refutations.

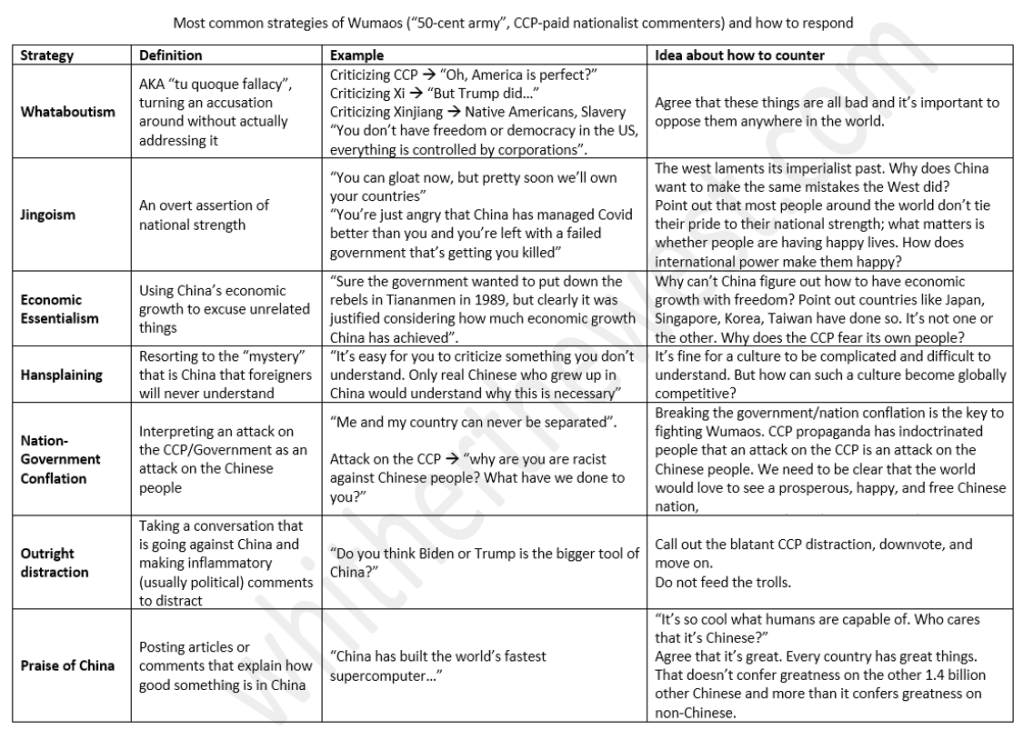

I compiled a handy guide to some of the most common strategies and talking points by Chinese nationalists online (on forums like twitter and reddit). [Sharable image first, copy-able text follows.] This list is far from exhaustive, but should be a good base for combating most arguments. Please share additional talking points or strategies in the comments.

One overriding thing to note: anyone in China has to use a VPN and violate Chinese law in order to be engaging on these forums in the first place. So don’t hesitate to draw attention to their hypocrisy and disrespect of Chinese law.

Update: This was posted on reddit, and the discussion there generated many more arguments and responses. Consider

These are really low hanging fruit. What about the more difficult points to combat that nationalists often make? How do we counter misinformation like this:

“It’s easy to criticize the CCP, but don’t the people have a right to say they want a government and society that is different from what Americans have? How do you promote freedom and human rights without also weakening the institutions that maintain China’s independence and uniqueness we value which many other countries have lost to globalization and westernization?”

“I think that the integration of China’s economy with the US has promoted the values we all want to see adopted by our government: free trade, freedom of movement, freedom of expression, etc. But now, the US is severing ties with China by imposing tariffs (even on goods like solar panels and EVs which are desperately needed to combat climate change), sanctioning and banning Chinese companies, and regressing to unfair trade practices like subsidizing domestic industry — practices it has criticized China for. How can the CCP in its current form be opposed when the good actors on the global stage like the US can’t be relied on to help in this fight and demonstrate correct behavior? How can we pressure the CCP when the US wants to punish China rather than shape China for the better?”

“Whenever the extremely high incarceration rate in the US is brought up, the disproportionate imprisonment of minorities there, or the forced labor practices the US and its state governments engage in, people always do whataboutism and say hush, you have no room to talk when the CCP is doing the same and worse in Xinjiang and Tibet. I think we should oppose human rights violations no matter where they happen in the world, but the conversation always gets turned to sanctions against China and opposing the CCP. In contrast, you’ve never heard someone say ‘it’s time for regime change in the US’ or ‘why not have sanctions against the US for its crimes’, and that’s because the US is still the global policeman, judge, jury, and executioner. It’s above reproach, above the law, and unaccountable to anyone. The US should be expected to be a state party to the Rome Statute; it should be expected to support and comply with the WTO; it should be a state party in the Paris Climate Accords all of the time, not just when it feels like it. If not for its military power, the US would be considered a rogue state.”

A (self-described) Chinese commenter replied to these points (my posting them here is not an endorsement):

As a Chinese person to answer these questions:

The Chinese people certainly have the right to choose a government that is different from that of the United States, but the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has not given the Chinese people the power to choose a government that is different from that of the CCP

The CCP has frantically suppressed civil society, from rights lawyers to investigative journalists to ordinary citizens. The CCP has used every means to crack down and persecute them. More than a decade ago, an old man took the initiative to monitor the misuse of public vehicles by officials. The CCP secret police lured him into prostitution with a scam and made it public. An attempt was made to ruin his reputation.

The CCP does not practice free trade. Take the communications industry for example. The CCP pretended to open up the communications industry when it joined the WTO, and after it joined the WTO, it opened up only a very small number of proliferating businesses. The same thing happened to the insurance industry. The CCP has formulated a series of “documents” to create a glass ceiling for foreign investment. Foreign investors are not allowed to participate in the most important insurance business at all. By contrast, it was not until the Trump era that the US government began to restrict Chinese telecoms operators from doing business in the US.

Liberalism itself encourages independence and uniqueness. Holding independence and uniqueness against Western civilisation, Hong Kong, the most liberal city in China, retains the most traditional culture. Under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party, people had been forced to destroy countless traditional cultures. They even destroyed the tomb of the legendary “Yellow Emperor”, the ancestor of the Chinese people. The independence that the CCP tries to retain is in fact their uninterrupted rule over the Chinese people.

Every country violates international law to a greater or lesser extent. But the United States remains the foremost defender of the international order. On the question of the US supporting Ukraine with tens of billions of dollars against the Russian invaders, China is supporting Russia on a massive scale. Including, but not limited to, massive prepaid energy orders, drones, industrial equipment.

Without further ado, the guide:

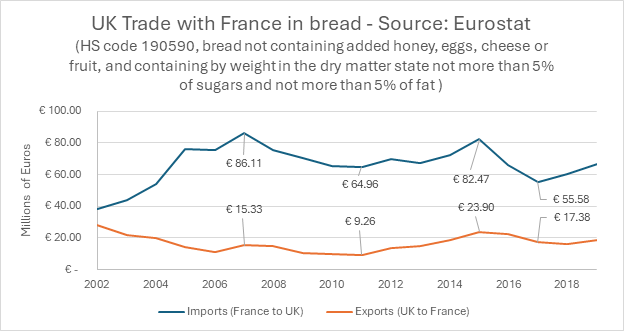

| Strategy | Definition | Example | Idea about how to counter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whataboutism | AKA “tu quoque fallacy”, turning an accusation around without actually addressing it | Criticizing CCP ➔ “Oh, America is perfect?” Criticizing Xi ➔ “But Trump did…” Criticizing Xinjiang ➔ Native Americans, Slavery “You don’t have freedom or democracy in the US, everything is controlled by corporations”. | Agree that these things are all bad and it’s important to oppose them anywhere in the world. |

| Jingoism | An overt assertion of national strength | “You can gloat now, but pretty soon we’ll own your countries” “You’re just angry that China has managed Covid better than you and you’re left with a failed government that’s getting you killed” | The west laments its imperialist past. Why does China want to make the same mistakes the West did? Point out that most people around the world don’t tie their pride to their national strength; what matters is whether people are having happy lives. How does international power make them happy? |

| Economic Essentialism | Using China’s economic growth to excuse unrelated things | “Sure the government wanted to put down the rebels in Tiananmen in 1989, but clearly it was justified considering how much economic growth China has achieved”. | Why can’t China figure out how to have economic growth with freedom? Point out countries like Japan, Singapore, Korea, Taiwan have done so. It’s not one or the other. Why does the CCP fear its own people? |

| Hansplaining | Resorting to the “mystery” that is China that foreigners will never understand | “It’s easy for you to criticize something you don’t understand. Only real Chinese who grew up in China would understand why this is necessary”. | It’s fine for a culture to be complicated and difficult to understand. But how can such a culture become globally competitive? |

| Nation-Government Conflation | Interpreting an attack on the CCP/Government as an attack on the Chinese people | “Me and my country can never be separated”. Attack on the CCP ➔ “why are you racist against Chinese people? What have we done to you?” | Breaking the government/nation conflation is the key to fighting Wumaos. CCP propaganda has indoctrinated people that an attack on the CCP is an attack on the Chinese people. We need to be clear that the world would love to see a prosperous, happy, and free Chinese nation. |

| Outright distraction | Taking a conversation that is going against China and making inflammatory (usually political) comments to distract | “Do you think Biden or Trump is the bigger tool of China?” | Call out the blatant CCP distraction, downvote, and move on. Do not feed the trolls. |

| Praise of China | Posting articles or comments that explain how good something is in China | “China has built the world’s fastest supercomputer…” | “It’s so cool what humans are capable of. Who cares that it’s Chinese?” Agree that it’s great. Every country has great things. That doesn’t confer greatness on the other 1.4 billion Chinese and more than it confers greatness on non-Chinese. |