Examining the History between Science and Christianity

During my early adulthood I was a zealous New Atheist, and as such believed wholeheartedly in a message that was central to the NA movement: that Christianity had been a parasite on Western civilization, dragging humanity into the Dark Ages and smothering science until skeptics and Enlightenment thinkers finally pulled us back into the light. While studying European history in depth, though, I began to see cracks in that story. The relationship between Christianity and science wasn’t as clear-cut as New Atheists made it out to be, and in some elements was rather constructive. But the question remained in my mind, and it grew into a larger curiosity about what made the West different—one that would eventually drive my MA studies in international economics and development.

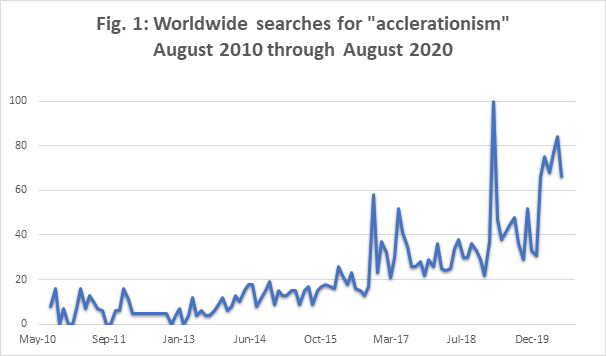

Recently, though, something surprising happened: I saw the old narrative resurface. If you were active in New Atheism circles in the 2000s (or honestly if you were active on the internet at all; to quote Scott Alexander, “I imagine the same travelers visiting 2005, logging on to the Internet, and holy @#$! that’s a lot of atheism-related discourse”) you probably saw a chart that looks something like this:

While many of those who were active New Atheists back in the early 2000s have mellowed out and found other ideological motivations (or disenchantments), it seems there is a new generation of zealous Atheists engaging with these ideas for the first time, and one secular group I saw the above graphic posted unironically, even with the ridiculous attribution of “Christian” dark ages. The resurfacing of that old certainty, combined with a provocative new scholarly article offering an economic perspective on Christianity’s role in scientific progress, prompted me to revisit the question. How exactly did Christianity interact with science throughout history? The answer is messier, and far more interesting, than the stories I once took for granted. I will tackle this in a way that is at once thematic and chronological: 1) the Dark Ages (or Early Middle Ages) 2) The (High) Middle Ages, and 3) the modern (Post-renaissance) world.

I. Did Christianity Cause the Dark Ages?

First, I want to address the easiest part of the question: did Christianity somehow cause the Dark Ages?

I think this can be answered very briefly with an unqualified “no”, and I will go even farther and say “quite the opposite”. I don’t know of any reputable modern historians who would say otherwise. Historically there have of course been literally hundreds of different causes blamed for the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the ensuing “Dark Ages”, including such obscure culprits as infertility, trade imbalances, loss of martial virtues, and wealth inequality. Yes, contemporaries in late antiquity did blame Christianity and the abandonment of traditional paganism for the fall of Rome. For example one of the last notable pagan scholars, the Eastern Roman historian Zosimus, put it plainly that “It was because of the neglect of the traditional rites that the Roman Empire began to lose its strength and to be overwhelmed by the barbarians.” (Historia Nova, Book 4.59), and most famously (Saint) Augustine of Hippo wrote his City of God to refute such perspectives (though he wrote before Zosimus): “They say that the calamities of the Roman Empire are to be ascribed to our religion; that all such evils have come upon them since the preaching of the Gospel and the rejection of their old worship.”(The City of God, Book 1, Chapter 1). Needless to say, these were not modern academic historians and were clearly making biased assertions based on the vibes of the day.

Today the historical consensus seems to be some combination of climate change-induced plague (see Harper, Kyle, “The Fate of Rome”), mismanagement by later emperors of the resulting chaos and malaise, and most importantly the Völkerwanderung, “The wandering of the peoples,” i.e. the migration of massive numbers of people from central and western Eurasia into Europe during the 4th and 5th centuries. To summarize the contemporary consensus into one sentence: the Western Roman Empire fell because decades of plague and civil war made it too weak to repulse or assimilate the entire nations of people migrating into Western Europe, and thus had to cut deals, cede territory, and slowly “delegate itself out of existence” (Collins, “Early Medieval Europe”). In direct refutation of the claim that Christianity caused the Dark Ages, the Christianization of these Germanic and other peoples was a vital channel for the transmission of culture and values and an important step toward (in Rome’s conception) civilizing and settling them in the Mediterranean world (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulfilas as one example).

As further refutation, the brightest spark of European Civilization during the Western European Dark Ages (roughly 500-800) was the Eastern Roman Empire, which was unquestionably *more* thoroughly Christian than the “Darkening” West. The Eastern empire boasted a stronger institutional religious structure, with the emperor himself dictating much of theological policy, and strongarm enforcement of official positions (e.g. with the Christological debates of late antiquity) was common: “The Byzantine emperor, always the head of the imperial hierarchy, automatically evolved into the head of this Christian hierarchy. The various bishops were subservient to him as the head of the Church, just as the governors had been (and were still) subservient to him as the head of the empire. The doctrines of the Christian religion were formulated by bishops at councils convened by the emperor and updated periodically at similar councils, with the emperor always having the final say” (Ansary, Tamim, “Destiny Disrupted”).

The Western empire, by contrast, struggled for centuries with institutionalization and conversion, with the Catholic church wrestling not just with latent paganism and heretical syncretism among rural populations but also an existential battle with Arian Christianity (a nontrinitarian form of Christianity that asserts that Jesus not an incarnation of God but merely a lesser creation of God), common for centuries among the ruling strata of Vandals and Goths in the early middle ages; “the Vandals were Arian Christians, and they regarded the beliefs of the Roman majority as sufficiently incorrect that they needed to be expunged… Arianism continued as the Christianity of ‘barbarian’ groups, notably Goths, Vandals and eventually Lombards, into the seventh century” (Chris Wickham, “The Inheritance of Rome”). Though I will risk overextending my argument here, I will say that the Church in fact prevented the Dark Ages from being even worse: “the Church emerged as the single source of cultural coherence and unity in western Europe, the cultural medium through which people who spoke different languages and served different sovereigns could still interact or travel through one another’s realms.” (Ansary).

There is a caveat to all this, though. Christianity did seem to have a deleterious effect on the logical philosophy of the late Empire. I have been able to find at least three separate early Christian philosophers who all deliver variation on the same idea that faith should triumph over logic and reason: “The nature of the Trinity surpasses all human comprehension and speech” (Origen, First Principles, Preface, Ch. 2); “If you comprehend it, it is not God” (Tertullian, De Carne Christi); and “I believe because it is absurd”, “Credo quia absurdum est” (Augustine of Hippo). But it is important to contextualize these perspectives in a general trend towards mysticism in late antiquity. Christianity was not alone, as Mithraism, Manicheism, Sun worship, and other prescriptive revealed religions swirled in the ideological whirlpool of late antiquity, and also to see the rise of all of the above as reactions to the declining state of the political economy: as we see evidenced today, material insecurity pushes people toward the comfort of religion (see e.g. Norris and Inglehart, Sacred and Secular).

II. Did Christianity Hinder or Help the Birth of Modern Science?

This question is somewhat more difficult to answer, and I originally had drafted much more, but decided to cut it down to prevent losing anyone in an overly academic morass. To summarize what I see as the answer to this question, there are two necessary components to the rise of modern science, the ideological and the structural. Ideologically, the quest to understand the divine plan through exploration of the natural world was common to both the Christian and Islamic proto-scientists, but when authorities decided this ideological quest was becoming threatening, structural changes that had taken place in Christendom (in part as a result of religious motivations) but not in the Caliphate saved proto-science in the former from the same fate as the latter. Thus Christianity initially helped, then became antagonistic toward emerging proto-science, but by the point that things got antagonistic, structural changes prevented the Church from effectively tamping out the proto-scientific sparks. Let’s expand a bit, but first a note about the Twelfth Century Renaissance.

In the west, the critical window here was the 12th Century Renaissance and the resulting changes that took place in the 13th century. The 12th Century Renaissance is less well-known than “The” Renaissance of the 15th century, but arguably had more far-reaching consequences in terms of laying the foundations of Western civilization and culture. “Although some scholars prefer to trace Europe’s defining moments back to the so-called Axial Age between 800 and 300 b.c., the really defining transformative period took place during the Renaissance of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. That is when the extraordinary fusion of Greek philosophy, Roman law, and Christian theology gave Europe a new and powerful civilizational coherence.” (Huff)

The Twelfth Century Renaissance witnessed two unrelated trends that came together at the end of the 13th century in one seminal decade, which I will unpack in later paragraphs. The first trend is the reintroduction (via translation schools in Toledo, Constantinople and the Papal States) of most of the works of Aristotle, giving birth to a “new intellectual discipline [that] came to be known as ‘dialectic.’ In its fully developed form it proceeded from questions (quaestio), to the views pro (videtur quod) and con (sed contra) of traditional authorities on a particular subject, to the author’s own conclusion (responsio). Because they subjected the articles of faith to tight logical analysis, the exponents of the new rational methods of study became highly suspect in the eyes of church authorities” (Ozment). The second trend was the rediscovery of Roman Law which triggered an immense restructuring of legal rights and entities in the entire Western world: “An examination of the great revolutionary reconstruction of Western Europe in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries shows that it witnessed sweeping legal reforms, indeed, a revolutionary reconstruction, of all the realms and divisions of law […] It is this great legal transformation that laid the foundations for the rise and autonomous development of modern science […]” (Huff).

We will examine how the novelties of the Twelfth Century Renaissance interacted to create the preconditions for Science as we know it, by examining the confluence of the two requirements, the ideological and the structural.

Ideologically, what was required for the creation of science was the attempt to use existing knowledge to understand the underlying structure of the world, i.e. the codification and understanding of the scaffold of natural laws that allowed an understanding of the way the world worked. The belief in a knowable creator god seems to have given rise to this concept in the Abrahamic world. In his “history of the world through Muslim eyes,” Destiny Disrupted, Tamim Ansary encapsulates that both Christian and Muslim proto-scientists shared the same goals of understanding God through natural observation: “As in the West, where science was long called natural philosophy, they [Abbasid-era Muslim philosophers] saw no need to sort some of their speculations into a separate category and call it by a new name[…]science as such did not exist to be disentangled from religion. The philosophers were giving birth to it without quite realizing it. They thought of religion as their field of inquiry and theology as their intellectual specialty; they were on a quest to understand the ultimate nature of reality. That (they said) was what both religion and philosophy were about at the highest level. Anything they discovered about botany or optics or disease was a by-product of this core quest[…]”. Islamic and European civilization both shared the Greek intellectual roots: “Greek logic and its various modes were adopted among the religious scholars.” (Huff) China, in contrast, along with the pre-Christian Mediterranean world, had admirable command of engineering principles and keen natural observation as exemplified by the likes of Zhang Heng, Archimedes, or Heron of Alexandria, but while visionary voices likely existed in each, neither Classical nor Chinese civilization generally adopted an ideological outlook that sought to comprehend what a bunch of discrete natural and engineering phenomena, such as the flow of water, motion of planets or architectural physics, might all say about the fundamental structure of the world or the will of the divine. To nail the issue even more tightly shut, “traditional Chinese mathematics was not abstract because the Chinese did not see mathematics in any philosophical sense or as a means to comprehend the universe. When mathematical patterns were established, they ‘were quite in accord with the tendency towards organic thinking’ and equations always ‘retained their connection with concrete problems, so no general theory could emerge’ (Olerich 22). In the west, in contrast, the Twelfth Century Renaissance added jet fuel to the existing ideological quest to create general theories and comprehend the universe: “In a word, by importing and digesting the corpus of the “new Aristotle” and its methods of argumentation and inquiry, the intellectual elite of medieval Europe established an impersonal intellectual agenda whose ultimate purpose was to describe and explain the world in its entirety in terms of causal processes and mechanisms” (Huff 152).

Structurally, what was required for the creation of modern science was the institutional independence of proto-universities to explore questions that ran contrary to social and religious dogmas. As historian Toby Huff explains, the new legal world created by the rediscovery of Roman legal codes was a veritable Cambrian explosion for European institutions and ideas

“For example, the theory of corporate existence, as understood by Roman civil law and refashioned by the Canonists and Romanists of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, granted legal autonomy to a variety of corporate entities such as cities and towns, charitable organizations, and merchant guilds as well as professional groups represented by surgeons and physicians. Not least of all, it granted legal autonomy to universities. All of these entities were thus enabled to create their own rules and regulations and, in the case of cities and towns, to mint their own currency and establish their own courts of law. Nothing like this kind of legal autonomy existed in Islamic law or Chinese law or Hindu law of an earlier era.” (Huff)

To expand, whereas up to the 12th century, the legal forms in Western Europe were almost wholly those that had been imported from Germanic feudal law, a highly personalist structure of fealty and dependence – land, businesses, countries, churches were the responsibility of individual lords, artisans, kings, bishops, what have you – who depended on their superiors for the mere right to exist. The idea of corporate personhood, that “corporations are people”, (putting aside all of the exploitative and oligarchic connotations it has taken on in the context of the American political scene in the 21st century) was a fascinating, powerful, liberating idea in the 12th century, and one that proved critical to the rise of modern science. Quickly towns, cities, mercantile ventures, and most critically cathedral schools, seminaries, and proto-universities strove to incorporate (literally, “to make into a body”) their existence in the Roman legal mold – no longer were they merely collections of people, they argued their way into being as legal entities distinct from their members and adherents. Further, the Catholic church enriched its canon law with Roman borrowings and promoted the creation of formal legal studies, for example at the University of Bologna. The Compounding with the ideological ferment after the reintroduction of Aristotle and other new texts, “European scholars began gravitating to monasteries that had libraries because the books were there[…] Learning communities formed around the monasteries and these ripened into Europe’s first universities.” (Ansary), which could then as independent corporate entities survive political or theological pressure on or from any individual member.

We can quite clearly examine the benefit of this arrangement by counterfactual comparison with Islamic society. Despite the fact that Islamic society also had a quest to understand the divine structure of the physical world and thus shared the same ideological perspectives that gave rise to proto-science, the very different institutional structure of the Islamic world resulted in a very different outcome for Islamic science. As philosophers began to question fundamental religious dogmas such as the necessity of revelation or the infallibility of the Quran, “the ulama were in a good position to fight off such challenges. They controlled the laws, education of the young, social institutions such as marriage, and so on. Most importantly, they had the fealty of the masses” (Ansary). The intellectual institutions such as Islamic awaqaf (plural of waqf, “pious endowment”) that did house these nascent intellectual pursuits were not legally independent but were the dependencies of individual sponsors who could apply pressure – or have pressure applied to them – and their very nature as pious endowments meant that “they had to conform to the spirit and letter of Islamic law” (Huff). Reaching higher into the political structure, In the 10th century, most of the Islamic world was united under the Abbasid Caliphate, and consequently a reactionary shift by the government could result in a persecution that could reach to most of the Islamic world. That is precisely what happened, for the Ulama used their influence to force a change in direction of the Caliphate. After a high tide of intellectual ferment, subsequent persecution of the scientist-philosophers under the next Caliph “signaled the rising status of the scholars who maintained the edifice of orthodox doctrine, an edifice that eventually choked off the ability of Muslim intellectuals to pursue inquiries without any reference to revelation.” (Ansary). And just to once again contrast with the Far East, “In China, the cultural and legal setting was entirely different, though it too lacked the vital idea of legal autonomy” (Huff). Most importantly in China, the dominance of the Civil Service Examinations served as a gravity well attracting all intellectual talent to a centralized, conservative endeavor, stifling other intellectual pursuits: “This was not a system that instilled or encouraged scientific curiosity […] The official Civil Service Examination system created a structure of rewards and incentives that over time diverted almost all attention away from disinterested learning into the narrow mastery of the Confucian classics.” (Huff 164).

Bringing this all together, in the West, the twin fuses of ideological ferment and corporate independence intertwined, and who else would light the spark aside from the Catholic church. As noted already, the Church realized the threat posed by the rising tide of Aristotelianism and its promotion of rigorous logical examination of the Church’s teachings. Whereas earlier in the 1200s the tendency was to try to find common ground between Aristotle and Christianity, or even to use them to reinforce each other as exemplified by Thomas Aquinas, by the latter part of the century conservative elements in the church saw Aristotelianism as an inherently hostile cancer, and in 1270 and again in 1277 they declared war, issuing (a reinforcing) a blanket condemnation of Aristotle. Historian Steven Ozment explains that “In the place of a careful rational refutation of error, like those earlier attempted by Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas, Bishop Tempier and Pope John XXI simply issued a blanket condemnation. The church did not challenge bad logic with good logic or meet bad reasoning with sound; it simply pronounced Anathema sit.”

The momentousness of this decision for the course of western thought cannot be overstated, for it represented an end to the attempt to reconcile theology and philosophy, science and religion. “Theological speculation, and with it the medieval church itself, henceforth increasingly confined itself to the incontestable sphere of revelation and faith[…] rational demonstration and argument in theology became progressively unimportant to religious people, while faith and revelation held increasingly little insight into reality for secular people.” (Ozment, Steven “The Age of Reform 1250-1550”). In short from 1277 onward, the religious got more religious, and the rational became more rational.

We see in action the importance of corporate independence and decentralized governance, because there were attempts to stamp out Aristotelianism: In England, there were attempts at Oxford in the late 13th century to restrict the teaching of certain Aristotelian texts. In 1282, the Franciscan Minister General Bonagratia issued statutes attempting to limit the study of “pagan” philosophy (mainly Aristotle) among Franciscan students. In the Dominican Order, after Aquinas’s death, there were some attempts by conservative members to restrict the teaching of his Aristotelian-influenced theology. The Dominican General Chapter of 1278 sent visitors to investigate teachers suspected of promoting dangerous philosophical doctrines. But these efforts failed, and universities proudly asserted their newfound legal independence: the University of Toulouse, which incorporated in only 1229, declared that “those who wish to scrutinize the bosom of nature to the inmost can hear the books of Aristotle which were forbidden at Paris” (Thorndike). The University of Padua became particularly known as a center for “secular Aristotelianism” in the late 13th and 14th centuries, and maintained a strong tradition of studying Averroes’ commentaries on Aristotle even when these were controversial elsewhere (Conti, Stanford).

But for the thinkers during and just after this time period, the intellectual whiplash stimulated new thought that truly began the rebirth of scientific thinking in the western world. Instead of blindly taking either the Church or Aristotle at face value, the idea that they could be in conflict gave rise to the idea that either or both could be wrong. The University of Padua mentioned above Scholars such as Jean Buridan or Nicole Oresme began their studies in religious matters (the former was a cleric and the latter a bishop) before turning to “scientific” studies, but their questioning of both religious and Aristotelian dogmas led them to pierce through accepted dogmas, making unique contributions to a wide variety of fields and generally considered to have lain the foundations for the coming scientific and Copernican revolutions.

III. How have science and religion reacted Post-Renaissance?

In a recent post on MarginalRevolution, economist Tyler Cowen linked a new article which tears this ancient quarrel new abroach, at least for the modern era. The opening statement concisely encapsulates the picture painted above: “Today’s leading historians of science have ‘debunked’ the notion that religious dogmatism and science were largely in conflict in Western history: conflict was rare and inconsequential, the relationship between religion and science was constructive overall”, and Cowen adds his commentary that “Christianity was a necessary institutional background”, as I believe the preceding section has shown. But the article by Matías Cabello picks up the story where I left off, and looks at the relationship after the Renaissance. Cabello sees the modern period as unfolding in three stages, with an increasingly secular perspective from the late Middle Ages until the Reformation, then a new period of increased religious fervor during the period of the Reformation and Wars of Religion (16th-17th centuries), finally relenting with the dawn of the Enlightenment in the early 18th century.

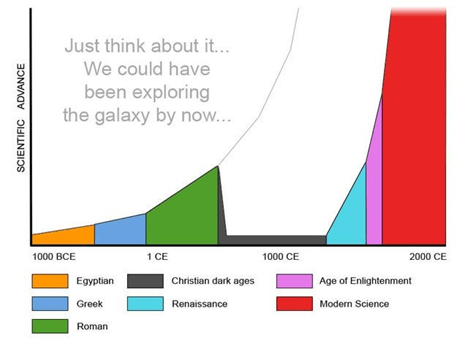

Cabello’s chronology lines up closely with my own knowledge of the topic, though I admit that after the Reformation my knowledge of this period is inferior to that of the previous eras. I draw primarily from Carlos Eire’s monumental and reputed book Reformations for knowledge of this period. But in general, there’s a lot of data showing that the Reformation was a much more violent, zealous, and unscientific time than the periods straddling it. A useful theory for understanding the dynamics of religion during this period is the Religious Market theory as formulated by Stark and Bainbridge (1987). In this theory, religions compete for adherents on a sort of market (or playing field, if you will), and in areas of intense competition, religions must improve and hone their “products” to stay competitive against other religions, but in areas where one religion monopolizes the market it becomes less competitive, vital, and active in the minds of adherents. This phenomenon is visible most clearly in the secularization of Scandinavian countries once Lutheranism enjoyed near complete monopoly for 400 years, and is often employed to explain why the pluralistic US is more religious than European countries which usually have one hegemonic church, but I would it argue it was also clearly at play in the Midde Ages. By the late Middle Ages, Catholicism enjoyed complete dominance in Western Europe against all rivals, allowing cynicism, political infighting (e.g. the western Schism which at one point saw three popes competing for recognition over the church), and, most critically, corruption to creep into the Church’s edifice. But when the Protestant Reformation broke out (in large part for the reasons just enumerated), suddenly there were several competing “vendors” who had to knuckle down and compete with each other and with different strands within themselves, leading to increased fanaticism and internecine violence for more than a century. There’s a lot of evidence that corroborates this general trend, for example Witch Hunts, which despite being portrayed in popular culture as a medieval phenomenon were decidedly a Reformation-era thing as shown in the below chart, (to wit, many of our popular ideas of the middle ages come from Enlightenment/Whig writers looking back on the 17th century and erroneously extrapolating from there).

If I can contribute my own assembled quasi “data set”, a few years ago I put together a western musical history playlist featuring the most notable composers from each time period, and one thing that clearly jumped out to me without being aware of this historical topography was that the music before the Reformation was much more joyous and open (and to my ears, just more enjoyable to listen to) than the rather conservative and solemn music that would come just after. To sum up, a lot of indicators tell us that the period of roughly 1500-1700 would have been a much less creative, openminded, and probably fun time to live than the periods just before or after.

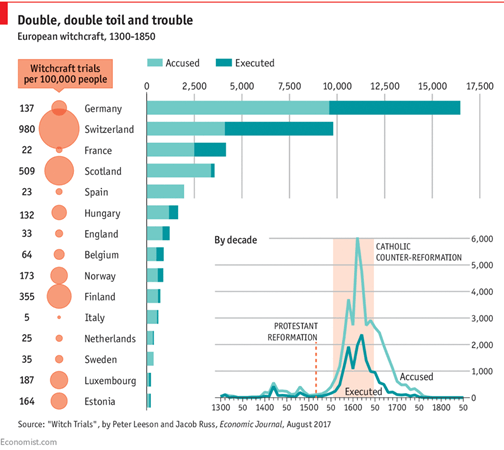

Getting back to Cabello, one of the novelties of his work is in its quantitative approach to what has traditionally been a very non-quantitative area of inquiry, scraping and analyzing Wikipedia articles to see how the distribution and length of science-related figures shifted over time. His perspective is most concisely presented by his figure B2, reproduced here:

To quote the author, “This article provides quantitative evidence—from the continental level down to the personal one—suggesting that religious dogmatism has been indeed detrimental to science on balance. Beginning with Europe as a whole, it shows that the religious revival associated with the Reformations coincides with scientific deceleration, while the secularization of science during the Enlightenment coincides with scientific re-acceleration. It then discusses how regional- and city-level dynamics further support a causal interpretation running from religious dogmatism to diminished science. Finally, it presents person-level statistical evidence suggesting that—throughout modern Western history, and within a given city and time period—scientists who doubted God and the scriptures have been considerably more productive than those with dogmatic beliefs.”

It is no coincidence, then, that the single most famous skirmish in history between science and religion, the trial and condemnation of Galileo Galilei, came squarely in the nadir of this fanatical period (1633).

And yet even in this context, science did, of course, continue to progress, and religious beliefs often lit the way. Historian of Science Thomas Kuhn produced what is likely the best analysis to date of how science progresses throughout the ages and how it is embedded in sociocultural assumptions. In his magnum opus, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions it is clear that the paradigm shifts that create scientific revolutions do not require secularization but rather the communion of different assumptions and worldviews. For example, the different worldviews of Tyco Brahe and Johannes Kepler, two Dutch astronomers who, as master and apprentice respectively, were looking at the same data but, with different worldviews, came to very different conclusions. Brahe believed that in a biblically and divinely structured universe, the earth must be at the center, and he as such rejected the new Copernican heliocentrism. His apprentice Kepler, however, also employed religious motivation, seeing the new heliocentric model as an equally beautiful expression of divine design, and one which squared more elegantly with the existing data and mathematics. Science, thus, is not about accumulating different facts, but looking at them through different worldviews. In one of my posts a few months ago, I mentioned that religious convictions and other reasons can push scientists to bend or break the scientific method, sometimes leading to scientific breakthroughs. One of the clearest examples was the scientific expedition of Sir Arthur Eddington, whose Quaker convictions likely made him see scientific discovery as a route towards global brotherhood and peace. In short the scientific method is an indispensable tool for verifying discoveries and we neglect it at our peril, but we must not let it become a dogma, for the initial spark of discovery often emanates from the deeply personal, irrational, cultural, or religious ideas of individuals.

In a recent blog post, Harvard professor of AI and Data Science Colin Plewis posted the following praise of Kuhn: “Far from the smooth and steady accumulation of knowledge, scientific advancement, as Kuhn demonstrates, often comes in fits and starts, driven by paradigm shifts that challenge and ultimately overthrow established norms. His concept of ‘normal science’ followed by ‘revolutionary science’ underscores the tension between tradition and innovation, a dynamic that resonates far beyond science itself. Kuhn’s insights have helped me see innovation as a fundamentally disruptive and courageous act, one that forces society to confront its entrenched beliefs and adapt to new ways of understanding.”

Conclusion

Hopefully this post has given a strong argument for the limited claim that Christianity is not a perennial enemy of science and civilizational progress. And perhaps it has also given some evidence for the idea that scientific advancement benefits from the contact and communication of different worldviews, assumptions, and frameworks of belief, and that Christianity, or religious belief in general, is not necessarily harmful for this broader project. Without question there can be places and times in which dogma, oppression, and fanaticism inhibit freedom of thought and impede the scientific project – but these can be found not only in the fanatical religious periods of the Wars of Religion or the fall of the Caliphates, but also in the fire of secular fanaticism such as Lysenkoism or the Cultural Revolution, or even the simple oppressive weight of institutional gravity, as was the case of the imperial exam system in China.

What can we take away from this historical investigation to inform the present and future?

Normally, we consider universities and affiliated research labs to be the wellsprings of scientific advancement in the modern West. But given that higher education in the united states demonstrates an increasing ideological conformity (a 2016 study found that “Democratic-to-Republican ratios are even higher than we had thought (particularly in Economics and in History), and that an awful lot of departments have zero Republicans”), Americans are increasingly sorting themselves into likeminded bubbles including into politically homogenous universities, preventing the confrontation with alternative worldviews that is the very stuff of free thought, creativity, and scientific progress. And since popular perceptions imply that this trend has only been exacerbated in intervening years, it may be that the “courageous act” of “revolutionary science” that “challenges and overthrows existing norms” may have to come from an ideological perspective outside the secular, liberal worldview of modern American academia. It may be that an overtly religious institution like a new Catholic Polytechnic Institute or explicitly Free Speech schools like the University of Austin, no matter how retrograde or reactionary they may appear to many rationalists, are the future of heterodox thinking necessary to effect the next scientific revolution.

Of course, the future of science will be inextricably linked to Artificial Intelligence, and it remains to be seen exactly what kind of role AI (or AGI or ASI) will play in the future of scientific discovery, leaving me with nothing but questions: (when) will AI have a curious and creative spark? Will it have a model of the universe, preconceptions and biases that determine how it deals with anomalous data and limit what and how it is able to think? Or will it have the computational power and liberty to explore all possible hypotheses and models at once, an entire quantum universe of expanding and collapsing statistical possibilities that ebb and flow with each new data point? And if, or when, it reaches that point, will scientific discovery cease to be a human endeavor? Or will human interpreters still need to pull the printed teletype from Multivac and read it out to the masses like the Moses of a new age?