International Causes and Effects of Portugal’s Democratic Transition

Author’s Note: I wrote this paper in 2014 as part of my MA program in International Studies, as part of my course on regime change. I am posting it now in commemoration of the 1974 Carnation Revolution and upon hearing news of a thorough new history of the revolution, The Carnation Revolution by Alex Fernandes. I am not a scholar or specialist of this particular revolution, but hope simply that this analysis may be of some use or inspiration to those who are.

Introduction

Portugal has, for its entire history, rested at the boundary between two worlds: from its creation, it occupied the dynamic intersection between Christian Europe and the Muslim World. Later, as a colonizing power, it was the doorway through which European ideas, peoples and goods flooded the rest of the world, and through which the world’s ideas, raw materials, and wealth entered Europe. In the twentieth century Portugal’s role as a gatekeeper took on a new meaning as it stood on the threshold between democracy and autocracy as both the last traditional European colonial empire and the country that began the Third Wave of Democracy.

Why did Portugal experience a democratic transition from 1974 to 1976? Why was the transition so peaceful and rapid? The question invites numerous theories, for Portugal is a unique and complex case. Valerie Bunce, in drawing her “big and bounded generalizations” about democratic transition, establishes regional rules but notes that Portugal was an obvious exception to the pattern of other Southern European transitions. This paper attempts to explain the whys. Ultimately we will see that transition was the result of the culmination of many factors, both domestic and external. Without discounting the importance of domestic causes, this paper aims to show that international causes were extremely important to both the beginning and outcome of the Carnation Revolution of 1974 to 1976. To do so it will first examine the nature of the regime and the circumstances surrounding its fall, then analyze them in the context of several mainstream theories of democratic transition.

The Regime

The regime was born in the economic woes of the Depression. “Under the first republic political and economic conditions had developed that favored a rightist takeover” including voter apathy, distrust of parliament, decline in individual wealth and fear of socialism” (Chilcote 29). António Salazar, a secluded and private clergyman-turned-politician, bought and manipulated media sources to create “an aura of financial infallibility” around himself which he used as a bargaining chip to be appointed Minister of the Treasury. In this post he cut down rivals in government and, cultivating alliances with both the Catholic Church and the military, attained the title of Prime Minister in 1932 (Birmingham 158). Under Salazar “the president served only in a ceremonial capacity” under the Prime Minister, the legislature was “subservient to the executive,” and Salazar’s regime, which by 1934 was known as the Estado Novo or “New State,” quickly produced a number of oppressive institutions such as “concentration camps for dissidents,” “an all-pervasive political police similar to…the German Gestapo,” and a new unifying ideology that stressed “an absolute and unquestioning respect for authority and all its agents, including the restored Catholic church.” There was even a “compulsory youth organization…modeled as a paramilitary group along the lines of its German and Italian counterparts” (Chilcote 33). Not surprisingly, the regime was almost universally described as fascist (Birmingham 158, Linz and Stepan 117, Ferreira and Marshall 7) by contemporaries.

Not all was as it seemed, however: almost all of the oppressive “fascist” institutions were perfunctory façades. Ideology was not a unifying melody, and there was no typical fascist drumbeat of military expansion and conquest. “The common aversion to pluralist democracy, and the violent treatment of opponents, masked differences of ideology and above all the absence of any Portuguese mass party which demagogues could rouse to attack ‘public enemies’” (Birmingham 159). Indeed, in contrast to the monolithic, society-encompassing workings of those states, the New State maintained a “democratic façade” that allowed small amounts of opposition, division, and protest (Chilcote 33). Further, “The Salazar regime in Portugal was not significantly different from the Franco regime in Spain. To be sure, the regime was at times described as totalitarian, but most scholars now concur that the regime never was totalitarian, even in the worst period under Salazar” (Linz and Stepan 117).

Given this diverse and rather contradictory set of institutions, it is difficult to find one label to encapsulate the nature of the regime at any one point. There is little doubt that the Estado Novo was, in the broad sense, an authoritarian regime. However, the search for more specificity about the nature of the regime leads to no academic consensus. It is therefore perhaps more useful to examine the nature of the regime as a dynamic historical entity. Arising in 1934 amidst the global political chaos of the Great Depression, the regime quickly modeled itself on the Fascist systems of Italy and Germany, creating secret police forces, a youth movement, a small cult of personality, and a party for national government and mobilization (Birmingham 163). However, quickly after the end of the Second World War and the fall of the model fascist regimes, the Estado Novo reversed course, and “In November 1945 the traditional opposition was born” as the state allowed some moderate parties and occasional (though perfunctory) elections (Machado 128).

In effect, the Estado Novo was a chameleon, adopting oppressive fascist institutions in a time of economic and political unrest and moderating the totalitarian tone after the violent end to fascism’s heyday. The latter tolerance of political parties and opposition movements are examples of “nominally democratic institutions” which serve the dual purpose of fostering a sense of legitimacy (to both internal and external observers) as well as co-opting rivals for power into the folds of the governing elite (Gandhi 41).

The Transition

The stroke and subsequent remove from politics of António Salazar in August 1968 marked the last chapter in the life of the Estado Novo. Though his successor, Marcelo Caetano, continued the same policies, Portugal’s continuing struggles to maintain control of its empire gradually became untenable. In February 1974 General António de Spinóla, commander of Portuguese troops in Guinea, published a book questioning the continued warfare for preservation of the empire and advocating a commonwealth-style arrangement. The book immediately struck chords with various junior officers in Portugal: some of whom had come to sympathize with the democratic rhetoric of the restive colonial subjects or had become disgusted with Portuguese repression, and others who were disillusioned with the lack of vertical mobility in the military – a pairing of common and classic grievances that may afflict the junior officer class (Demirel 2005). Further, “their own conditions began to make them aware of the conditions faced by the vast majority of the people. They began to interpret their grievances in political terms” (Bruneau 1974). On April 25th, a mere two months after the publication of the book, military forces loyal to the left-leaning MFA (Movimento das Forças Armadas – Armed Forces Movement) entered Lisbon, occupied important locations and buildings, and peacefully deposed the government, immediately ending military occupation in Africa and beginning a process of democratization that, aside from a rightist counter-coup inspired by fears of an “anti-democratic communist putsch” in November 1975, proceeded in a peaceful and stable fashion (Birmingham 179).

The curious aspect of this democratic transition is not only the relative absence of instability or a struggle for power, but rather the fact that it proceeded without any significant pacting between the elite and opposition. “Pacting” in this sense is “an explicit, but not always publicly explicated or justified, agreement among a select set of actors which seeks to define (or, better, redefine) rules governing the exercise of power on the basis of mutual guarantees for the ‘vital interests’ of those entering into it” (O’Donnell and Schmitter 1986 p 37). Or, to put it more simply, when a country’s political elites sense that the regime’s days are numbered, they may cut deals or offer concessions in order to preserve their own power or at least end up with the best possible outcome. According to Valerie Bunce in her comparison of paths of democratization, “pacting between authoritarian elites and leaders of the opposition forces is the mode of transition that seems to maximize the prospects for quick and sustained democratization in Latin America and southern Europe,” and further that “between regime transitions that bridge authoritarian and democratic rule and those that involve a sharp break with the authoritarian past…the first approach [i.e. pacting] has tended to be the most successful in producing full-scale and sustainable democracies in the south” (Bunce 716-7). However, Bunce mentions several times that “Portugal [is] clearly exceptional” and “the Portuguese case gives pause.” It is somewhat anomalous, then, when Bunce draws her overarching rule that “all new democracies confront the same three issues: breaking with authoritarian rule, building democratic institutions, and devising ways to elicit the cooperation of the former authoritarian elite” but does not grant Portugal an exception to that rule (Bunce 715). And indeed this pattern did not play out in the case of Portugal. According to Linz and Stepan (p 116), Portugal experienced the first two steps, “breaking with authoritarian rule” and “building democratic institutions” at the same time: they experienced a “simultaneous transition and consolidation”. Why? Linz and Stepan provide a very detailed account of the endogenous factors for the successful transition including that “the official party was not strongly organized,” that “the military were more unruly,” and that there were “regular elections to a parliament and even a short period of tolerated political contestation before the elections,” but in regards to foreign intervention that sources “require more research” (L&S 116, 117,126).

The following pages will attempt to do just that. This investigation will first discuss the concept of Democratic Linkage

Linkage and Leverage

Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way propound what they see as a dichotomy of “leverage” or coercive pressures and “linkage” or persuasive pressures that favor democratization – sticks and carrots, respectively. In their conception, “leverage” may be phenomena such as “political conditionality and punitive sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and military intervention.” “Linkage,” in turn, is a measure of the “density of [a country’s] ties to the United States, the EU, and Western-dominated multilateral institutions” along lines such as trade, migration, media, or civil society. Though Levitsky and Way note that “the end of the Cold War posed an unprecedented challenge to authoritarian regimes” and as such developed the linkage/leverage model with an eye toward the changed realities of post-Cold War geopolitics, the theory is (or at least first became) at least partially applicable in the case of Portugal’s 1974 Carnation Revolution in ways which I will expound.

Levitsky and Way mention that “Western powers have played a distinctly positive role in promoting democracy throughout much of the world” though that assertion comes with the caveat “since the end of the Cold War.” In regards to leverage, Levitsky and Way are correct that coercive promotion of democracy was rare before the end of the Cold War, whose geopolitical realities severely hampered democratic governments’ abilities to “leverage” authoritarian regimes. Though “political conditionalities” or “punitive sanctions” saw sporadic use such as in the US embargo on Cuba (which was primarily anti-Communist rather than pro-Democracy, though later US rhetoric in the OAS would argue the opposite), the West did not employ alternatives like “military intervention” to install democracy. Why? Partially because such interventions would serve as a tacit endorsement of the Soviet Union to militarily expand communism, but mostly because the West viewed authoritarianism as an acceptable alternative to communism, as Jeanne Kirkpatrick’s 1979 “Dictatorships and Double Standards” exemplified.

In the case of linkage, on the other hand, the interconnections of economies, societies, and cultures played an extremely large role in fostering the growth of democracy even as early as the Carnation Revolution at the very outset of the Third Wave of Democracy. As later sections shall show, the economic and sociopolitical ties between Portugal and the US and EEC proved critical in bolstering Portuguese democracy during its period of regime transition.

Socioeconomic Linkage

1) The deepening legitimacy problems of authoritarian regimes in a World where democratic values were widely accepted, the consequent dependence of these regime on successful performance, and their inability to maintain “performance legitimacy” due to economic (and sometimes military) failure.

Samuel Huntington, first two causes of the Third Wave of Democratization

2) The unprecedented global economic growth of the 1960s, which raised living standards, increased education, and greatly expanded the urban middle class in many countries.

The exogenous economic causes of the Carnation Revolution take two distinct forms, and both voluntarist and structuralist perspectives provide strong evidence that exogenous factors were crucial in Portugal’s peaceful democratic transition. Portugal provides a unique testing ground for two theories concerning regime stability: first, that economic development promotes democratization, and second, that economic downturn undermines the stability of autocratic regimes. The role that economic growth and expansion plays in the process of democratic transition and development has been the subject of academic debate for decades and falls largely into two categories: structuralism and voluntarism.

The structural perspective is closely related to the modernization school (as exemplified by W.W. Rostow) in its theory that economic growth precipitates sociocultural changes that serve to horizontalize power structures and make democratic participation more desirable and common. To quote Ingelhart and Welzel (2009), “high levels of economic development tend to make people more tolerant and trusting, bringing more emphasis on self-expression and more participation in decision making.” This theory shares much in common with the psychological principle of the Hierarchy of Needs, which argues that as individuals’ basic physiological and material needs are better met, their needs shift to more abstract needs such as societal respect and self-expression (Maslow 1943). It is important to note, however, that structuralism is not parsimonious and that “this process is not deterministic, and any forecasts can only be probabilistic, since economic factors are not the only influence” (Ingelhart and Welzel 2009).

In contrast to the structural perspective on democratization is the voluntarist school, which focuses, as its name suggests, not on the impersonal trends and forces such as economic development but rather on the conscious choices of actors, namely the political elites of a regime. As Samuel Huntington declares, “democratic regimes that last have seldom, if ever, been instituted by mass popular action;” that is, lasting democratic institutions are produced by the “James Madisons” and other “political leaders.” (Huntington (3) 212), or, as Burton et al. put it, “the consolidation of a new democracy requires the establishment of elite consensus and unity” (323). To see how voluntarism interacts with economic trends, one can turn to the literature not on democratic transition but rather on the stability of authoritarian regimes. “In a modern authoritarian regime…a leader… must distribute selective rewards to loyalists and impose selective punishments on rivals” (Slater 86). Or, more broadly speaking, an authoritarian government depends on economic surplus to maintain control:

“Availability of economic resources also decreases the probability of coups and of political destabilization. Correspondingly, higher levels of per capita income and stronger economic growth are associated with authoritarian stability. When dictators have the resources to induce cooperation from powerful groups within the elite and to fund a patronage system to co-opt the citizens, the state remains stable. When they lack these resources, they ‘cannot pay their civil servants (who may therefore turn to corruption) or their armed forces (who may then use their weapons to pay themselves)’.” (Magaloni and Kricheli 2010 (inline citations omitted))

That is, political elites maintain their positions by harnessing economic gains and distributing them for political support. We will see shortly how this proved to backfire on the Portuguese elites in the latter stages of the Estado Novo.

Let us first analyze the theoretical framework and then see how it applies in the case of Portugal. Though an initial gloss of voluntarist and structuralist approaches may find them to be diametrically opposed, a synthesis of the structuralist and voluntarist views on democratization would see these two forces working in harmony: on a long timeframe (for example, on the order of decades or centuries) economic growth allows for a more mobile and dynamic society that builds civic institutions and demands greater rights, liberties, and means of representation. In contrast, on a short timeframe (that is, on the order of months or years) economic growth or decline can respectively either bolster or diminish a population’s material wealth and comfort and thus the authoritarian elite’s resources, legitimacy, and ability to maintain control. Thus, structuralism and voluntarism in democratization theory are not mutually exclusive or incompatible, but merely focus on democratization from different timescales and with different ratios of proximal and distal rationales. How, then, do these theories (or their synthesis) apply to the Portuguese case?

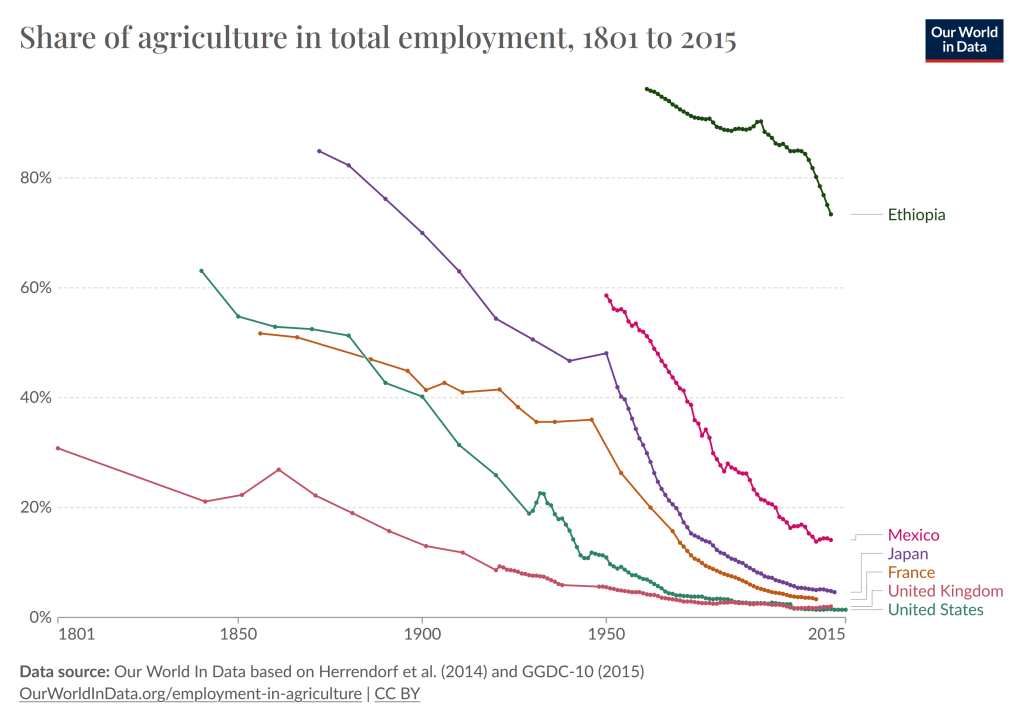

First, on a structural level, the Portuguese economy, like those of other Southern European democracies-to-be, grew rapidly in the 1960s and early 1970s. As Huntington phrases it, “In the two decades before their transitions in the mid-1970s, Spain, Portugal, and Greece experienced explosive economic growth,” (Huntington (2) 68) and other sources indicate that “the annual average rate of increase of the GDP was above 6 percent [through the 60s]” – “the secondary sector [e.g. manufacturing and refining] averaged a growth rate of 9 percent annually [between 1961 and 1973]” (Machado 21). This economic growth was not due to domestic successes but rather to the exogenous global economic boom of the time period: “the third wave of democratization was propelled forward by the extraordinary global economic growth of the 1950s and 1960s” (Huntington 311).

However, these economic gains were not evenly distributed – quite the contrary. Indeed, “until the fall of the reactionary coalition, economic concentration and power were located in the monopolistic core” and few economic gains accumulated to the average Portuguese citizen (Machado 33). Further, “the benefits from Portugal’s economic growth which were not eaten up by Lisbon’s colonial wars accrued largely to the small cluster of controlling families” (Hunt 6). A glaring exception, however, was the military, which “consumed greater quantities of consumer goods” throughout the 60s and early 70s due to public spending on colonial wars (Machado 20). Though ongoing military conflict and external trade facilitated massive industrialization and rapid growth throughout the time period, the economic problems were not merely distributional, but also structural. Portugal was dangerously dependent on foreign oil, and thus an exogenous economic downturn helped precipitate the instability of the regime: “The oil price hike of 1973-74 triggered a global economic recession…it significantly undermined the efforts of Third World authoritarian regimes to use economic performance to bolster their legitimacy;” interestingly Huntington uses the term “Third World” here, though in the next sentence declares that “countries such as the Philippines, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Brazil, and Uruguay were particularly hard hit.” Whether or not Huntington intends to group Southern Europe into the Third World is beside the point – at issue is the fact that a sudden economic downturn spelled the end of the regime’s stability (Huntington 51). Huntington continues that in dealing with the oil shock, “authoritarian government…often made the economic situation worse, producing stagnation, depression, inflation [etc.]” and such is precisely what occurred in Portugal: “there were large deficits in the nation’s balance of payments. By late 1973 inflation had soared, and hundreds of thousands of workers had emigrated to other parts of Europe” (Chilcote 84). This vastly facilitated one element of the democratic linkage and will be discussed in more detail below.Before analyzing the results of those linkages, let us first consider the voluntarist angle.

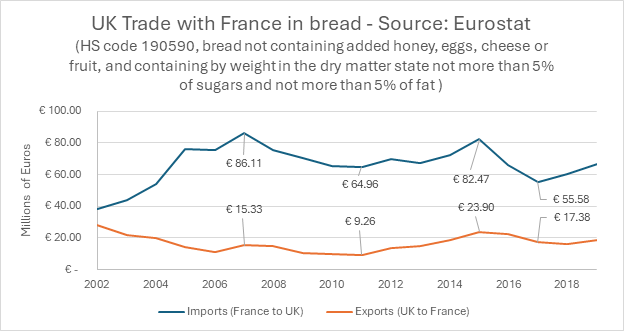

From the voluntarist perspective, democratic linkage played a crucial role. As mentioned above, a primary source of democratic linkage is international commerce and trade: countries and peoples who engage in business transactions will invariably exchange some ideas and values, and it stands to reason that the larger the volume of these transactions, the higher the rate of ideational exchange (Levitsky and Way 23). The Portuguese case demonstrates this principle to great effect.

Seemingly paradoxically, during the era of the Estado Novo, the desire for closer relations with Europe was a rightist, non-democratic concept. Though this may seem initially backwards, the rationale is not difficult to follow: the element of society that stood to gain the most from the desired economic growth was the business elite who already controlled Portugal’s large businesses, sprawling farms, and international trade. Integration with Europe was seen “as one means of meeting the increasing commercial and technological needs” of the ruling monopolies – needs that were increasingly difficult to produce domestically (Chilcote 60). In addition, the Portuguese left, largely represented by the socialists and communists, were heavily focused on domestic development, the rights of small-scale landowners, and greater protections for domestic industrial workers (which often implied higher tariffs).

These same attitudes held true during and immediately after the 1974 Carnation Revolution. The rightist counterrevolutionary groups supported capitalist revitalization and “integration with Europe and a sacrifice of national interests to the European Economic Community” (Chilcote 239). In addition, the first provisional government after the April 25th coup, which comprised moderate rightist elements, sought to “intensify relations with the EEC, and establish diplomatic relations with all countries” (Chilcote 96). At the same time, however, pursuing closer ties with Europe was a double-edged sword, as it widened the avenues for democratic linkage. As relations with Europe became closer, democratic ideals spread freely. As the avenues widened even further, economic integration turned to wholesale migration:

“There was an increasing tendency, particularly after Caetano took office in 1968, for government technicians and businessmen to turn to Europe with hopes of ultimately joining the EEC. This definite propensity to look less to Africa and more to Europe for Portugal’s economic future was in a way illustrated by the massive emigration, caused not by a pro-European attitude on the part of the population but by a comparison of conditions at home with those abroad” (Bruneau 1974).

Very quickly, as travel, commerce, and migration between Portugal and the rest of Europe blossomed, popular desire for an insulated, domestic outlook waned. Before examining the larger political causes and effects thereof, let us first recapitulate on the economic democratization theories – namely the structuralist theory that economic development promotes democracy and the voluntarist theory that economic downturn undermines autocratic legitimacy. Regarding the development-democratization hypothesis, Portugal presents a complicated case study. Though the country as a whole did experience high rates of economic growth in the years leading up to the Carnation Revolution, that growth was inordinately confined to the existing political and economic elite and did not trickle down to the democratic elements of society or facilitate their ascendance on the Hierarchy of Needs. The notable exception is, of course, the military, which received a disproportionate share of the economic benefits yet and was the element of society that ultimately enacted the April 25th coup. The direction of causality here is unclear (was the revolution despite or because of the economic gains to the military class?) but of immense interest, as it would either confirm or contradict the structuralist developmental theory of democratization.

In addition, the voluntarist (in the elite-centric sense) model of democratization simply did not occur in the Portuguese case, as the Carnation revolution represented a clean break with the past that did not incur elite pacting behavior, as Valerie Bunce mentions above.

To gain some insight we can examine interviews from within the very ranks of the MFA. One Lieutenant Colonel, Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, mentions that he joined the movement of captains because of contact with officers who had “been to universities” and in order to prevent the “erosion of privileges” of the officer class (Ferreira and Marshall 115). Another Lieutenant Colonel, Vasco Lourenco, argues that “army officers also felt that they had lost prestige with the Portuguese people, for they were seen as supporters of both the regime and the colonial war. The oposição had managed to convince people that the officers gained from the war in terms of salaries, etc.” however, he does not offer evidence as to whether such gains actually occurred (Ferreira 134). However, the idea is contradicted by political scientist Thomas Bruneau who states that “their salaries were not high and the rampant inflation ate into them severely” (Bruneau 282) and Portuguese Major Mário Tomé counters the socioeconomic argument for the coup in saying that “the war was the most important factor” in the officers’ politicization (Ferreira and Marshall 155).

Though this evidence leaves the developmental democracy idea without much direct support in the case of Portugal, the facts strongly favor the idea that the economic decline, exogenous in origin (though amplified by domestic structures) crippled all legitimacy and sustainability of the Estado Novo. Rampant inflation and inequality undermined any elite claims to power based on economic growth, and served to unite both officers of many different social backgrounds into a certainty that the regime’s time had come.

Regardless of the theoretical interpretations the fact remains that by mid-decade opposition to European Integration had declined and “in…Portugal in the mid-1970s there was a pervasive desire to identify…with Europe…Almost half of Portugal’s foreign trade was with the [European Economic] Community” (Huntington (2) 88). What exactly caused such a radical change in people’s views in such a short period of time? Can economics alone explain the shift in desire and identity towards a pro-European course of action? On the contrary, although the proliferation of ties with Europe allowed critical comparisons to arise and democratic notions to permeate Portugal, it was the direct political involvement of European and American political forces that allowed Portugal to steer clear of violence, chaos, and instability in its democratic transition.

Political Linkage

3) A striking shift in the doctrine and activities of the Catholic Church, manifested in the Second Vatican Council of 1963-65 and the transformation of national Catholic churches from defenders of the status quo to opponents of authoritarianism.

Samuel Huntington, third and fourth causes of the Third Wave of Democratization

4) Changes in the policies of external actors, most notably the European Community, the United States, and the Soviet Union.

In 1974, in the immediate aftermath of the coup, the interim government began a withdrawal of troops from its African colonies (Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau), ending a centuries-old empire that remained the last European empire in Africa. Despite the massive territorial losses, the end of the empire brought a decision about its role in the world. “With the collapse of the Empire…Portugal was faced with the choice between integration into Europe and finding its own path” (Chilcote 60). As mentioned above, the initial view of the Portuguese democratic left was for a concentration on domestic affairs and not greater integration with Europe. However, major incentives awaited for the latter choice. As Huntington puts it,

During the third wave, the European Community (EC) played a key role in consolidating democracy in southern Europe. In Greece, Spain, and Portugal, the establishment of democracy was seen as necessary to secure the economic benefits of EC membership, while Community membership was in turn seen as a guarantee of the stability of democracy. In 1981, Greece became a full member of the Community, and five years later Spain and Portugal did as well. (Huntington (1) p.14)

However, as Huntington goes on to say, intervention “was not limited to passively providing an economic incentive and political anchor” but active political involvement on the part of European political parties. (Huntington (2) 89). Every major political party in the revolutionary period maintained close connections with their European counterparts (Ferreira 209-216). In order to counter both the Portuguese Communist Party funded by Moscow and the remaining rightist factions and parties, “The European socialist parties…by funds, organizational links, and moral support, bolstered the most important democratic party in Portugal, the Socialists led by Mario Soares” (Linz and Stepan 127). The EEC and – after being dissuaded by the EEC from military intervention (Linz and Stepan 127) – the US both extended political aid packages to shore up the moderate Socialist against both the counterrevolutionary right and the far left Communist party. EEC Aid was given in response to Portugal’s return to “pluralistic democracy” and US aid was in “support for political evolution in Portugal” as well as for Angolan refugees which the US helped airlift to Portugal. European socialist leaders, including François Mitterand who would become President of France in 1981, visited Portugal to support the Portuguese Socialist Party, which “grew rapidly” with external support (Ferreira and Marshall 212). The CIA, restricted in its activities due to congressional investigation, resorted to “the transfer of secret funds…through Western European social democrats” (Chilcote 232). In addition, Moscow also heavily contributed to the Portuguese Communist party, which directly precipitated the rightist countercoup of 1975 (Hunt 115-117) which may have been undertaken with the tacit support of the CIA (Chilcote 231-232). However, there was among MFA interviewees, “reluctance…to discuss the degree of foreign intervention in the revolution” (Ferreira and Marshall 202).

Samuel Huntington places special emphasis on the linkage provided by the Catholic church and credits a change in policy of the Holy See with drastically impacting democratization in Portugal and elsewhere. He labels the Third Wave of democracy as a “Catholic Wave” (Huntington (1) 13) and argues that by switching from a position of tolerating authoritarianism to decrying it,“Rome delegitimated authoritarian regimes in Catholic countries” (Huntington book 86). In contrast, interviews with Portuguese military personnel reveal that “only a few officers mention” the involvement of the Catholic Church in Portugal’s revolution, even though it decidedly “played a political role” in the north of the country and was strongly tied to the “Maria de Fonte Movement, which blew up several of the local headquarters of the PCP [Portuguese Communist Party]” (Ferreira and Marshall 202).

All in all, “external actors significantly helped third wave democratizations” (Huntington 86). Though endless wars of colonial preservation overheated and overburdened the country’s economy and military resulting in the end of the Estado Novo, the revolutionary forces that were unleashed thereafter had little certainly of integrating with Europe and pursuing a liberal democracy. After all, the 1975 coup was based on fears of a communist takeover. However, moderate parties, specifically the Socialist party, received large influxes of aid and support from the EEC and US, resulting in their very prominent (though not hegemonic) role in Portuguese politics to this day. And after the revolution had concluded, “the European community became a valuable and steady pole of attraction for Portuguese democratic governments” (Linz 127)

Would the Carnation Revolution have played out the same way without the influence of Foreign Actors? It is difficult to say. However, Portugal serves as an interesting case study as it is the tip of the spear: the first of the Third Wave of democratization. And what is certain is that the Portuguese example enormously affected the way the rest of the Third Wave transpired.

Linkage effects

5) “Snowballing,” or the demonstration effect of transitions earlier in the third wave in stimulating and providing models for subsequent efforts at democratization.

Samuel Huntington, fifth cause of the Third Wave of Democratization

In discussing the rapid spread of uprisings against Saddam Hussein following the expulsion of Iraqi troops in the First Gulf War, James Quinlivan noted that “While this speed of propagation is certainly faster than movement on foot, it hardly matches the speed of light of the communications revolution” (Quinlivan 30). This line of reasoning echoes Huntington in that “the tremendous expansion in global communications” made it “increasingly difficult for authoritarian governments to keep from their elites…information on the struggles against and overthrow of authoritarian regimes in other countries” (Huntington (2) 101). As the first regime change in the Third Wave of Democratization, Portugal broke new ground, which is exactly why Valeria Bunce labels it as “exceptional”.

How exactly did Portugal’s transition change the trajectory of others? It did so by the simple fact that, from the perspective of a dictator or ruling elite, “the Portuguese upheavals were…a point of reference of how not to make a transition” (Linz and Stepan 117). As no pacting took place and the coup quickly and easily removed the ruling elites from power, elites in other countries looked for avenues to optimize their positions vis-à-vis a democratic transition. As the quote from Samuel Hunting at the beginning of this section illustrates, this process “snowballed” – that is to say, with each country that transitioned to democracy, the more inevitable it appeared that such changes would proceed to another country, and thus the more likely the elites of any country would be to engage in pacting and initiate a democratic transition.

If we are to believe Linz and Stepan that “the more tightly coupled a group of countries are, the more a successful transition in any country in the group will tend to transform the range of perceived political alternatives for the rest of the group,” it would make sense that Portugal’s closest neighbor, Spain, would be the quickest to learn the lessons of the Carnation Revolution, and that is indeed exactly what occurred. “After the Portuguese revolution had exploded, a Spanish conservative leader, Manuel Fraga, expressed some interest in playing a role in leading democratic change because he ‘did not want to become the Caetano of Spain’” (Linz 76). Spain, in turn, as the second democratization of the Third Wave, became the first country to have the opportunity to learn the lessons of Portugal and thus the “paradigmatic case for the study of pacted democratic transition” (Linz and Stepan 87). Ironically, the political learning surrounding the Carnation Revolution was not unidirectional: in a humorous 1976 parallel, in a conversation with Henry Kissinger concerning Communist influence in the government, Portuguese Prime Minister Mário Soares lamented that he did not “want to be a Kerensky,” to which Kissinger shot back, “neither did Kerensky,” (a point which served to a great extent to illustrate the brashness of American policy in Portugal) (Maxwell 6). The same lessons, perhaps also accompanied by the ensuing independence and initial democratization of Portugal’s colonial holdings, rippled out across the rest of the world, for “international diffusion effects can change elite political expectations, crowd behavior, and relations of power within the regime almost overnight” (Linz & Stepan 76). Indeed, with few exceptions, the countries of the third wave did not follow the Portuguese path. As Valeria Bunce describes it, in the rest of Southern Europe and South America, “pacting, the composition of the interim government, and the outcome of the first competitive election all functioned as bridges between the authoritarian past and the democratic future” and negotiated democratization became the international norm (717).

Conclusions

The Portuguese transition to democracy from 1974 to 1976 was the result of a confluence of many factors. The goal of this paper was to demonstrate that international factors were chief amongst them. Let us recapitulate and reconsider some of the findings.

Despite Levitsky and Way’s claims that the Linkage and Leverage model is only applicable in the international environment of the post-Cold War era, there are certainly aspects of it that are applicable in the Cold War era. The wars of colonial suppression and the closer economic ties that Portuguese oligarchs pursued for their own personal gain both served to be double-edge swords in that they provided access to goods and markets but also served as conduits, or elements of linkage, through which democratic ideals could infiltrate Portuguese society. And indeed, the alleged threat of US military intervention strongly resembles the “post-Cold War” mechanism of democratic leverage, though directed against communism rather than autocracy. After the initial coup which toppled the regime, the continued close ties with the EEC, European political parties, and the US government served as masts that held aloft the democratic sails of the new democracy, preventing the gales of either the extreme left or extreme right from overturning it.

Economically, as well, the fate of the Estado Novo was never purely domestic in nature, but rather tied to the success of the global market: the legitimacy of the regime was built on industrial expansion in the sixties, but after the oil shocks of the early 1970s, the regime clung to an increasingly tenuous hold on power and legitimacy, and the strain on the domestic economy, coupled with the disproportionate expenditure on military endeavors, overburdened both military and democratic populous.

Rehashing some of the conclusions from earlier, it would seem that the developmental model of democratization – that is to say, the idea that increasing economic and material wealth moves a people up the hierarchy of needs and into a state of mind that demands greater individual rights and capacities for self-expression and self-government – garners little evidence from the Portuguese case. Or rather, the general developmental or structuralist model of democratization does not account for the distribution of wealth within a society. Though Portugal gained enormously in raw economic productivity during the 1960s, that productivity accrued primarily to the ruling elite and not to the general public. One could argue, perhaps, that structuralist model of democracy is valid regardless of the distributional breakdown because in either case it results in democratization: either directly by bettering the material existence and prospects of the people, or indirectly, by accruing to the elite and thus increasing disdain for, and diminishing the legitimacy of, the regime in the eyes of the people. Following that line of reasoning further, however, may lead one to view structuralist factors of democratization in a post hoc ergo propter hoc fashion – if economic development occurs, and democratization later comes to pass, the development is responsible for the democratization regardless of intervening factors.

The opposite economic argument – that is, that economic downturns presage instability and collapse for autocratic regimes – seems to claim a wealth of evidence from Portugal. After the increase in the price of imported oil that Portugal was relatively very dependent on, the economy, overheated from wars and stratified in favor of the autocratic elite, had few resources at its disposal to buy loyalty or passivity from would-be democrats. The military faced the twin problem of having been denied economic wealth but having earned the reputation of having doing so, and in many ways the coup was a defense of military honor and standing in society.

In any case, however, there were no guarantees that a coup, even a successful one, would lead to a peaceful democratic outcome, and to that end numerous external factors took part. European political parties contributed aid and guidance. The US contributed both aid and strong political pressure. The EEC provided a strong long-term incentive and beacon of identification around which the disparate new political force could coalesce and agree.

Finally, the Carnation Revolution stands out in the textbooks as the first of the Third Wave – that is, the revolution set a precedent that is in many ways being followed to this day in the case of Eastern Europe and the Middle East. The global networks of information and communication that helped spread the Portuguese spark to Spain and many countries around the world in the 70s, 80s and 90s have taken new shape in the form of Twitter, Facebook and Youtube. Furthermore the Portuguese case gave the impression to many political elites around the world that democracy is inevitable, and in the first leg of the Third Wave, most elites learned that lesson and pacted and negotiated their way out of authoritarianism. By setting that example, who can guess how many democratic movements Portugal inspired, or how many lives it saved by encouraging peaceful transition to democracy.

Works Cited

| Birmingham, David. A Concise History of Portugal. Cambridge University Press. New York. 2003. |

| Bruneau, Thomas. The Portuguese Coup: Causes and Probable Consequences. The World Today. Vol. 30, No. 7, Jul., 1974. |

| Bunce, Valerie. Comparative Democratization: Big and Bounded Generalizations. Comparative Political Studies. 2000. |

| Burton et al. Elites and Democratic Consolidation in Latin America and Southern Europe. Cambridge University Press. 1991. |

| Chilcote, Ronald. The Portuguese Revolution. State and Class in the Transition to Democracy. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc. Plymouth. 2010. |

| Demirel, Tanel. Lessons of Military Regimes and Democracy: The Turkish Case in a Comparative Perspective. Armed Forces and Society. 31:245. 2005. |

| Ferreira, Hugo and Michael Marshall. Portugal’s Revolution: Ten Years On. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 1986. |

| Gandhi, Jennifer. Political Institutions under Dictatorship. Cambridge University Press. 2010. |

| Hunt, Christ. Portuguese Revolution 1974-76. Facts on File, Inc. New York. 1976. |

| Huntington, Samuel (1). Democracy’s Third Wave. Journal of Democracy. Vol 2. No. 2. Spring 1991. |

| Huntington, Samuel (2). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press. 1991. |

| Huntington, Samuel. “Will More Countries Become Democratic?” Political Science Quarterly 99. Spring 1984. |

| Ingelhart and Welzel. How Development Leads to Democracy: What We Know About Modernization. Foreign Affairs, Vol. 88, No. 2. April 2009 |

| Linz, Juan and Alfred Stepan. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore. 1996. |

| Machado, Diamantino. The Structure of Portuguese Society: The Failure of Fascism. Praeger Publishers. New York. 1991. |

| Magaloni and Krichelli. Political Order and One-Party Rule. Annual Review of Political Science. 13:123-43. 2010. |

| Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396. 1943. |

| Maxwell, Kenneth. Portuguese Defense and Foreign Policy: An Overview. Camoes Center for the Study of the Portuguese-Speaking World. 1991. |

| O’Donnell, Guillermo and Philippe Schmitter. Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore. 1986, 2013. |

| Quinlivan, James. Coup-proofing: Its Practices and Consequences in the Middle East. International Security,Vol. 24, No. 2 pp. 131–165. 1999. |

| Slater, Dan. Iron Cage in an Iron Fist: Authoritarian Institutions and the Personalization of Power in Malaysia. Comparative Politics, Vol. 36, No. 1 pp. 81-101. 2003. |